Artists & Artisans

De Lempicka, Tamara

| “In her paintings everything is caressed with love and a meticulous brush... Her paintings remind us of the classics in museums but with infinitely more seduction and sensitivity. This is not really realistic painting: she could be called realistic if the term were enlarged. Her art is not cold despite its precision. Her portraits are alive and even hallucinatory.” - Critic for Conmedia on May 22, 1930 |

Once described as the “most known unknown artist,” Tamara de Lempicka was a key figure in the Art Deco movement, whose luxurious neo-Cubist paintings left an indelible mark on fine art and pop culture of the 1920s and 1930s. With a life full of uprooting and re-establishing, De Lempicka harnessed her disturbed beginnings into passionate artmaking. Through dynamic portraits of modern society women and herself, coupled with geometrically influenced works of nude figures, De Lempicka created a name for herself as a woman always on the cutting edge of society with her unique style.

While her canon had somewhat fallen into obscurity in the decades after her peak creative years, renewed interest in Art Deco and an increasing focus on female artists of the 20th century is rightfully pushing De Lempicka back into the limelight.

Early Life

Tamara Rosa Hurwitz was born in Warsaw, Poland (then the Congress Poland of the Russian Empire) in 1894. Her father was a Russian-Jewish banking attorney, which afforded the family to live a wealthy, high-class lifestyle while Tamara was growing up. Her mother, Malwina, was a Polish-Jewish socialite, and she raised Tamara with the help of Tamara’s grandparents after her father disappeared from her life.

At age 10, Tamara’s mother commissioned a local artist to do a pastel portrait of her daughter. Unfortunately for the artist, Tamara was headstrong and stubborn from the start, and she detested sitting and posing for such long periods of time. When the artist finished, Tamara was unhappy with the work and made it known by taking the pastels, posing her younger sister, and creating her first-ever portrait.

Although her parents sent her to boarding school in Lausanne, Switzerland, at age 13, Tamara found the school inadequate and feigned illness in an attempt to return to her family in Warsaw. Instead, her grandmother took her on a tour of Italy, where she was exposed to the Old Masters, who molded her interest in art. Later in her career, she would harness this early exposure by blending her portraits with the luminescence intrinsic to Italian Renaissance paintings.

Beginnings in St. Petersburg, Russia

In 1915, while staying with her aunt in St. Petersburg, Tamara met and fell in love with Tadeusz Łempicki, an important lawyer to the Czar court. After a year of courting, the two married in the Chapel of the Knights of Malta when Tamara was 16. Luckily for Tadeusz, who had very little money to his name, he received a large dowry in the marriage. From that point, Tamara assumed her life would be that of a married socialite, enjoying the splendors of the royal court and society in Russia’s capital. The two had their only child on September 16, 1916, a daughter named Maria Krystyna “Kizette.”

Unfortunately for Tamara, in November 1917, the Bolshevik Russian Revolution completely overturned her comfortable future. One month later, Tadeusz was arrested in the middle of the night by the secret police for his ties to the Czar. Although Tamara was able to secure a release for Tadeusz through the Swedish consul, enduring her own tribulations in that period of trying to garner favor with political officials, the two were no longer safe in Russia and were forced to exile from what had always been their homeland.

A New Life in Paris

When the Russian Revolution happened, Tamara’s family in Warsaw fled to Paris to escape persecution as members of the cultural elite. Thus, the Łempicki’s chose to reunite with Tamara’s family in Paris and make a new name for themselves in France. This period of time was extremely hard for Tamara. Instead of living an upper-class life in Russian society, Tamara found herself in a foreign country, was relatively penniless, and felt desperate to provide a good life for her daughter. In the beginning, the family relied on the sales of their jewels to get by; however, this only went so far, and Tadeusz struggled immensely to find work.

|

Portrait of a Polo Player by De Lempicka. 1922. Oil on canvas. Private Collection.

|

While sharing her grievances with her sister Adrienne about their financial situation, Adrienne suggested she harness her passion for art for financial benefit. Taking that suggestion into stride, she began studying at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere and Académie Ranson under Maurice Denis and André Lhote, the father of neo-Cubism. In order to contribute to her family’s living situation, she immediately began selling still-lifes and portraits of her daughter Kizette through Galerie Collete-Weil while also exhibiting at salons for promising young painters, such as the Salon des indépendents. In the early beginnings of her career, she signed her name in the masculine form, “Lempitzki,” to increase her chances of selling works.

Breakout and Finding Success

In 1925, Tamara, who had by this point changed her name to De Lempicka to bring an aristocratic quality to her personal image, when she exhibited at the Salon des Tuileries and Salon des femmes peintres. The International of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts was held in 1925 in Paris, known as the birthplace of Art Deco, and Tamara’s works were noticed by leading American magazines and found favor with upper-class members of the public. That same year, Tamara had her first solo exhibition in Milan.

|

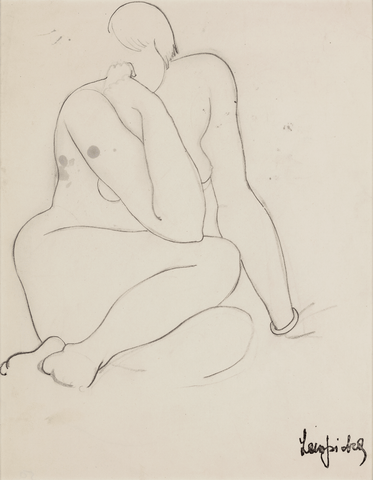

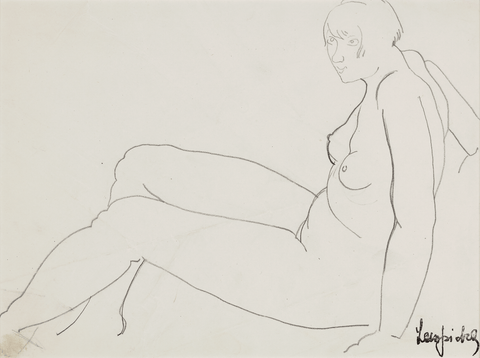

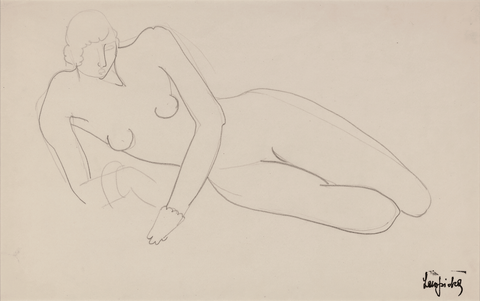

Smiling Nude by De Lempicka. Circa 1928. Pencil on paper. M.S. Rau.

|

As Tamara’s great-granddaughter remarks, “She became a portrait painter to make a living. It was a means to survive.” Self-noted as a workaholic, Tamara often worked nine-hour days to complete three sessions with different models. Tamara was commissioned extensively by writers, journalists, Parisian women, exiled members of the Eastern European nobility, and more to paint their portraits. It was in portraits of women that Tamara truly excelled.

In Tamara’s female portraits, she harnessed the spirit of the Roaring 20s and Art Deco to present her subjects with glamor, power, and a sense of confidence and individuality. She embraced Cubism’s theory of painting simplified forms and based her paintings on the simplicity of spheres and cylinders. Using her paintbrush, she created outlines of the figure from brushstrokes and, with the lightness of the Renaissance, developed a luminescent quality to the paint that made her subject glow with sensuality.

|

Portrait of Romana de la Salle. 1928. Oil on canvas. Private Collection.

|

The start to her success in 1925 continued to pick up speed, and in 1927, Tamara won the first prize at the Exposition Internationale des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, France, for her portrait Kizette on the Balcony. Her success also opened the doors to Paris’ bustling social scene, where she became a frequent party guest at the raging events around the city. She also began having affairs with men and women, many of whom would become models for her, such as the subject of La belle Rafaëla (1927).

|

La belle Rafaëla by De Lempicka. 1927. Oil on canvas. Private Collection, Paris.

|

In the late 1920s, Tamara also began studying nude models and painting cubist nude works that explored the poise and grace of the naked body. Her figures, mainly women, were boldly cosmopolitan in their straightforward gaze toward the viewer and confident poses that suggested both sensuality and power. However, she portrayed their bodies as highly idealized and smoothly polished, almost glowing as if bathed in theatrical lights. As Magdeleine Dayot wrote in 1935, Tamara’s works were a “curious blend of extreme modernism and classical purity, [that] attracts and surprises…”

| Les Deux Amies by De Lempicka. 1930. Oil on panel. Sold at Christie’s in 2020 for $9,405,500. |

Her self-made success, coupled with her various affairs, led to the disintegration of her marriage with Tadeusz, leading to divorce in 1928. With the help of high-profile portrait commissions, she purchased an apartment on rue Méchain near Montparnasse in a community of other artists and creatives and continued to raise her daughter amidst the onslaught of work.

A short while after Tamara divorced her husband, she was commissioned to paint a portrait of Spanish dancer Nana de Herrera, the mistress of Raoul Kuffner, a baron from the former Austro-Hungarian empire. Upon its completion, the two hit it off and began a long and devoted relationship that would last until his death in 1961. While their relationship remained private as an extramarital affair at first, when the Baron’s wife died in 1933, the two married the next year.

The Great Depression and Onset of WWII

In 1928, Tamara painted one of her most iconic works, Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti), which epitomized the glamorous energy of the 1920s. Commissioned by the German magazine Die Dame to celebrate the independence of women, she shows herself in the Cubist style, driving a Bugatti in a high-fashion leather ensemble. Her slitted eyes, which pierce the viewer, emulate a cold air of eliteness, effortless beauty, and wealth.

| Autoportrait (Self-Portrait in a Bugatti) by De Lempicka. 1928. Oil on panel. Private Collection, Switzerland. |

Unfortunately for Tamara, the raucous energy of the 1920s came crashing down when the stock market failed in the United States in 1929. Despite the financial stability of the Great Depression, her success peaked at the beginning of the 1930s. Tamara exhibited a popular one-woman show at the Galerie Collete-Weil in Paris. She was commissioned to paint portraits of royalty, such as those of Queen Elizabeth of Greece and King Alfonso XIII of Spain. In 1933, she traveled to Chicago and exhibited alongside American artists Georgia O’Keefe and Willem de Kooning, where she found inspiration in the cityscapes of urban America.

By the mid-1930s, though, something had changed in the preferences of Tamara’s customer base. The Great Depression was affecting everyone acutely, and her subjects of glamorous and carefree women were not as popular. In an effort to maintain relevancy, Tamara changed her subjects to religious and lower-class figures, though these did not garner the same attention. Then, in 1939, with the onset of World War II looming, Tamara became increasingly incensed by the rise of Nazis and the threat to Jewish people. She convinced her husband to sell most of his properties in Hungary and move his fortune to Switzerland for safekeeping. In 1939, she and Baron moved to the United States, narrowly avoiding the Vichy regime of Paris in 1940.

Setting Roots in America

Tamara and Baron Kuffner first settled in Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, where she was nicknamed the “Baroness with a Paintbrush.” Tamara began showing works in the Julian Levy Gallery in New York, the Paul Reinhard Gallery in Los Angeles, and the Courvoisier Gallery in San Francisco. Halfway through the war, in 1943, the two relocated to New York City.

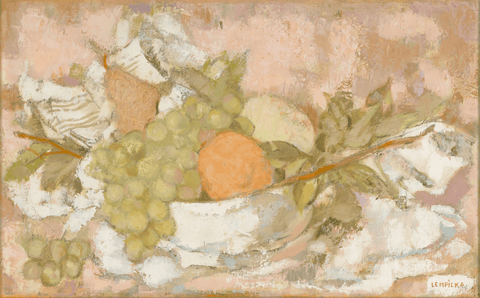

When the war ended, Tamara’s art deco painting style was anachronistic to the post-war industrialism and abstract expressionism that broke onto the scene in the 1950s. While she received fewer portrait commissions, Tamara expanded her subjects to still-lifes and landscapes and began experimenting with abstraction. Using a palette knife, in contrast to her usual smooth brushwork, Tamara created nonobjective paintings that focused on texture and color.

|

Abstract Painting in Blue and Orange by De Lempicka. 1950. Oil on canvas. M.S. Rau (sold).

|

Later Years

In 1961, Baron Kuffner died of a heart attack while on a ship en route to New York. Heartbroken by the loss of her dear husband, Tamara sold the majority of her possessions and spent two years making three around-the-world trips on ocean liners.

|

Le Bouquet de Lilas (Lilac Bouquet) by De Lempicka. Circa 1962. Oil on canvas. M.S. Rau.

|

Works during her travels expanded on her textural studies with thick applications of paint depicting still-lifes and landscapes, such as Le Bouquet de Lilas (c. 1962). At the end of her world tours, Tamara moved to Houston, Texas to live with her daughter Kizette and her husband, Texan geologist Harold Foxhall. At this time, she officially retired from a career as a professional artist and dedicated herself to her family.

In the late 1960s, a revival of Art Deco appeared and Tamara’s works received a resurgence of appreciation. In 1972, the Luxembourg Gallery in Paris showed a retrospective of her works which was met with critical acclaim.

While no longer a professional artist, the Art Deco painter continued to create and often returned to compositions of her past for reworking. In 1974, Tamara used to life always on the move, decided to move to Cuernavaca, Mexico. Between 1974 and 1979, Tamara repainted her 1929 Autoportrait twice.

On March 14, 1980, Tamara de Lempicka passed away.

The De Lempicka Legacy

Even after Tamara’s death, her works continued to be shown and purchased. Celebrities like Madonna collect her works, and Madonna bragged in a 1990 interview with Vanity Fair, “I have a Lempicka museum.” She most recently featured a De Lempicka oil painting for the set of her 2023 Celebration Tour world tours. A stage play, “Tamara,” ran for 11 years in Los Angeles (1984-1995), making it the longest-running play in the city.

|

Portrait of Tamara. 1939.

|

Art museums around the world have collected De Lempicka, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Museum in Krakow, Poland, which exhibited her works from September 2022 to March 2023, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, among others. Starting in October 2024, the Fine Arts Museums in San Francisco will host the first major US retrospective of Tamara de Lempicka’s works.

Tamara De Lempicka’s works of the 1920s, characterized by a carefree spirit and powerful independence for the female subjects she highlighted, continue to have an enduring influence on modern art and the pop culture landscape. Tamara’s life, marked by her constant redefinitions of self, reflects her ground-breaking modern femininity and power as one of the defining painters of the Art Deco movement.

Today, Tamara de Lempicka’s paintings are highly sought after by fine art collectors worldwide, capturing the elegance and intensity of the Art Deco era. M.S. Rau proudly offers a curated selection of her original works. For more details, please contact us today.

Artists & Artisans

De Lempicka, Tamara

| “In her paintings everything is caressed with love and a meticulous brush... Her paintings remind us of the classics in museums but with infinitely more seduction and sensitivity. This is not really realistic painting: she could be called realistic if the term were enlarged. Her art is not cold despite its precision. Her portraits are alive and even hallucinatory.” - Critic for Conmedia on May 22, 1930 |

Once described as the “most known unknown artist,” Tamara de Lempicka was a key figure in the Art Deco movement, whose luxurious neo-Cubist paintings left an indelible mark on fine art and pop culture of the 1920s and 1930s. With a life full of uprooting and re-establishing, De Lempicka harnessed her disturbed beginnings into passionate artmaking. Through dynamic portraits of modern society women and herself, coupled with geometrically influenced works of nude figures, De Lempicka created a name for herself as a woman always on the cutting edge of society with her unique style.

While her canon had somewhat fallen into obscurity in the decades after her peak creative years, renewed interest in Art Deco and an increasing focus on female artists of the 20th century is rightfully pushing De Lempicka back into the limelight.

Early Life

Tamara Rosa Hurwitz was born in Warsaw, Poland (then the Congress Poland of the Russian Empire) in 1894. Her father was a Russian-Jewish banking attorney, which afforded the family to live a wealthy, high-class lifestyle while Tamara was growing up. Her mother, Malwina, was a Polish-Jewish socialite, and she raised Tamara with the help of Tamara’s grandparents after her father disappeared from her life.

At age 10, Tamara’s mother commissioned a local artist to do a pastel portrait of her daughter. Unfortunately for the artist, Tamara was headstrong and stubborn from the start, and she detested sitting and posing for such long periods of time. When the artist finished, Tamara was unhappy with the work and made it known by taking the pastels, posing her younger sister, and creating her first-ever portrait.

Although her parents sent her to boarding school in Lausanne, Switzerland, at age 13, Tamara found the school inadequate and feigned illness in an attempt to return to her family in Warsaw. Instead, her grandmother took her on a tour of Italy, where she was exposed to the Old Masters, who molded her interest in art. Later in her career, she would harness this early exposure by blending her portraits with the luminescence intrinsic to Italian Renaissance paintings.

Beginnings in St. Petersburg, Russia

In 1915, while staying with her aunt in St. Petersburg, Tamara met and fell in love with Tadeusz Łempicki, an important lawyer to the Czar court. After a year of courting, the two married in the Chapel of the Knights of Malta when Tamara was 16. Luckily for Tadeusz, who had very little money to his name, he received a large dowry in the marriage. From that point, Tamara assumed her life would be that of a married socialite, enjoying the splendors of the royal court and society in Russia’s capital. The two had their only child on September 16, 1916, a daughter named Maria Krystyna “Kizette.”

Unfortunately for Tamara, in November 1917, the Bolshevik Russian Revolution completely overturned her comfortable future. One month later, Tadeusz was arrested in the middle of the night by the secret police for his ties to the Czar. Although Tamara was able to secure a release for Tadeusz through the Swedish consul, enduring her own tribulations in that period of trying to garner favor with political officials, the two were no longer safe in Russia and were forced to exile from what had always been their homeland.

A New Life in Paris

When the Russian Revolution happened, Tamara’s family in Warsaw fled to Paris to escape persecution as members of the cultural elite. Thus, the Łempicki’s chose to reunite with Tamara’s family in Paris and make a new name for themselves in France. This period of time was extremely hard for Tamara. Instead of living an upper-class life in Russian society, Tamara found herself in a foreign country, was relatively penniless, and felt desperate to provide a good life for her daughter. In the beginning, the family relied on the sales of their jewels to get by; however, this only went so far, and Tadeusz struggled immensely to find work.

|

Portrait of a Polo Player by De Lempicka. 1922. Oil on canvas. Private Collection.

|

While sharing her grievances with her sister Adrienne about their financial situation, Adrienne suggested she harness her passion for art for financial benefit. Taking that suggestion into stride, she began studying at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere and Académie Ranson under Maurice Denis and André Lhote, the father of neo-Cubism. In order to contribute to her family’s living situation, she immediately began selling still-lifes and portraits of her daughter Kizette through Galerie Collete-Weil while also exhibiting at salons for promising young painters, such as the Salon des indépendents. In the early beginnings of her career, she signed her name in the masculine form, “Lempitzki,” to increase her chances of selling works.

Breakout and Finding Success

In 1925, Tamara, who had by this point changed her name to De Lempicka to bring an aristocratic quality to her personal image, when she exhibited at the Salon des Tuileries and Salon des femmes peintres. The International of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts was held in 1925 in Paris, known as the birthplace of Art Deco, and Tamara’s works were noticed by leading American magazines and found favor with upper-class members of the public. That same year, Tamara had her first solo exhibition in Milan.

|

Smiling Nude by De Lempicka. Circa 1928. Pencil on paper. M.S. Rau.

|

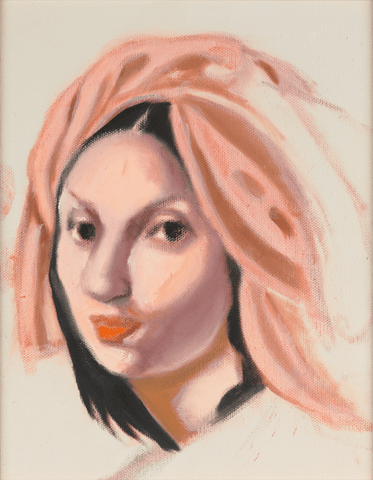

As Tamara’s great-granddaughter remarks, “She became a portrait painter to make a living. It was a means to survive.” Self-noted as a workaholic, Tamara often worked nine-hour days to complete three sessions with different models. Tamara was commissioned extensively by writers, journalists, Parisian women, exiled members of the Eastern European nobility, and more to paint their portraits. It was in portraits of women that Tamara truly excelled.

In Tamara’s female portraits, she harnessed the spirit of the Roaring 20s and Art Deco to present her subjects with glamor, power, and a sense of confidence and individuality. She embraced Cubism’s theory of painting simplified forms and based her paintings on the simplicity of spheres and cylinders. Using her paintbrush, she created outlines of the figure from brushstrokes and, with the lightness of the Renaissance, developed a luminescent quality to the paint that made her subject glow with sensuality.

|

Portrait of Romana de la Salle. 1928. Oil on canvas. Private Collection.

|

The start to her success in 1925 continued to pick up speed, and in 1927, Tamara won the first prize at the Exposition Internationale des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, France, for her portrait Kizette on the Balcony. Her success also opened the doors to Paris’ bustling social scene, where she became a frequent party guest at the raging events around the city. She also began having affairs with men and women, many of whom would become models for her, such as the subject of La belle Rafaëla (1927).

|

La belle Rafaëla by De Lempicka. 1927. Oil on canvas. Private Collection, Paris.

|

In the late 1920s, Tamara also began studying nude models and painting cubist nude works that explored the poise and grace of the naked body. Her figures, mainly women, were boldly cosmopolitan in their straightforward gaze toward the viewer and confident poses that suggested both sensuality and power. However, she portrayed their bodies as highly idealized and smoothly polished, almost glowing as if bathed in theatrical lights. As Magdeleine Dayot wrote in 1935, Tamara’s works were a “curious blend of extreme modernism and classical purity, [that] attracts and surprises…”

| Les Deux Amies by De Lempicka. 1930. Oil on panel. Sold at Christie’s in 2020 for $9,405,500. |

Her self-made success, coupled with her various affairs, led to the disintegration of her marriage with Tadeusz, leading to divorce in 1928. With the help of high-profile portrait commissions, she purchased an apartment on rue Méchain near Montparnasse in a community of other artists and creatives and continued to raise her daughter amidst the onslaught of work.

A short while after Tamara divorced her husband, she was commissioned to paint a portrait of Spanish dancer Nana de Herrera, the mistress of Raoul Kuffner, a baron from the former Austro-Hungarian empire. Upon its completion, the two hit it off and began a long and devoted relationship that would last until his death in 1961. While their relationship remained private as an extramarital affair at first, when the Baron’s wife died in 1933, the two married the next year.

The Great Depression and Onset of WWII

In 1928, Tamara painted one of her most iconic works, Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti), which epitomized the glamorous energy of the 1920s. Commissioned by the German magazine Die Dame to celebrate the independence of women, she shows herself in the Cubist style, driving a Bugatti in a high-fashion leather ensemble. Her slitted eyes, which pierce the viewer, emulate a cold air of eliteness, effortless beauty, and wealth.

| Autoportrait (Self-Portrait in a Bugatti) by De Lempicka. 1928. Oil on panel. Private Collection, Switzerland. |

Unfortunately for Tamara, the raucous energy of the 1920s came crashing down when the stock market failed in the United States in 1929. Despite the financial stability of the Great Depression, her success peaked at the beginning of the 1930s. Tamara exhibited a popular one-woman show at the Galerie Collete-Weil in Paris. She was commissioned to paint portraits of royalty, such as those of Queen Elizabeth of Greece and King Alfonso XIII of Spain. In 1933, she traveled to Chicago and exhibited alongside American artists Georgia O’Keefe and Willem de Kooning, where she found inspiration in the cityscapes of urban America.

By the mid-1930s, though, something had changed in the preferences of Tamara’s customer base. The Great Depression was affecting everyone acutely, and her subjects of glamorous and carefree women were not as popular. In an effort to maintain relevancy, Tamara changed her subjects to religious and lower-class figures, though these did not garner the same attention. Then, in 1939, with the onset of World War II looming, Tamara became increasingly incensed by the rise of Nazis and the threat to Jewish people. She convinced her husband to sell most of his properties in Hungary and move his fortune to Switzerland for safekeeping. In 1939, she and Baron moved to the United States, narrowly avoiding the Vichy regime of Paris in 1940.

Setting Roots in America

Tamara and Baron Kuffner first settled in Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, where she was nicknamed the “Baroness with a Paintbrush.” Tamara began showing works in the Julian Levy Gallery in New York, the Paul Reinhard Gallery in Los Angeles, and the Courvoisier Gallery in San Francisco. Halfway through the war, in 1943, the two relocated to New York City.

When the war ended, Tamara’s art deco painting style was anachronistic to the post-war industrialism and abstract expressionism that broke onto the scene in the 1950s. While she received fewer portrait commissions, Tamara expanded her subjects to still-lifes and landscapes and began experimenting with abstraction. Using a palette knife, in contrast to her usual smooth brushwork, Tamara created nonobjective paintings that focused on texture and color.

|

Abstract Painting in Blue and Orange by De Lempicka. 1950. Oil on canvas. M.S. Rau (sold).

|

Later Years

In 1961, Baron Kuffner died of a heart attack while on a ship en route to New York. Heartbroken by the loss of her dear husband, Tamara sold the majority of her possessions and spent two years making three around-the-world trips on ocean liners.

|

Le Bouquet de Lilas (Lilac Bouquet) by De Lempicka. Circa 1962. Oil on canvas. M.S. Rau.

|

Works during her travels expanded on her textural studies with thick applications of paint depicting still-lifes and landscapes, such as Le Bouquet de Lilas (c. 1962). At the end of her world tours, Tamara moved to Houston, Texas to live with her daughter Kizette and her husband, Texan geologist Harold Foxhall. At this time, she officially retired from a career as a professional artist and dedicated herself to her family.

In the late 1960s, a revival of Art Deco appeared and Tamara’s works received a resurgence of appreciation. In 1972, the Luxembourg Gallery in Paris showed a retrospective of her works which was met with critical acclaim.

While no longer a professional artist, the Art Deco painter continued to create and often returned to compositions of her past for reworking. In 1974, Tamara used to life always on the move, decided to move to Cuernavaca, Mexico. Between 1974 and 1979, Tamara repainted her 1929 Autoportrait twice.

On March 14, 1980, Tamara de Lempicka passed away.

The De Lempicka Legacy

Even after Tamara’s death, her works continued to be shown and purchased. Celebrities like Madonna collect her works, and Madonna bragged in a 1990 interview with Vanity Fair, “I have a Lempicka museum.” She most recently featured a De Lempicka oil painting for the set of her 2023 Celebration Tour world tours. A stage play, “Tamara,” ran for 11 years in Los Angeles (1984-1995), making it the longest-running play in the city.

|

Portrait of Tamara. 1939.

|

Art museums around the world have collected De Lempicka, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Museum in Krakow, Poland, which exhibited her works from September 2022 to March 2023, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, among others. Starting in October 2024, the Fine Arts Museums in San Francisco will host the first major US retrospective of Tamara de Lempicka’s works.

Tamara De Lempicka’s works of the 1920s, characterized by a carefree spirit and powerful independence for the female subjects she highlighted, continue to have an enduring influence on modern art and the pop culture landscape. Tamara’s life, marked by her constant redefinitions of self, reflects her ground-breaking modern femininity and power as one of the defining painters of the Art Deco movement.

Today, Tamara de Lempicka’s paintings are highly sought after by fine art collectors worldwide, capturing the elegance and intensity of the Art Deco era. M.S. Rau proudly offers a curated selection of her original works. For more details, please contact us today.