Artists & Artisans

Degas, Edgar

Early Life

Born to a wealthy Parisian family, Edgar Degas began his artistic career as an average student; however, he would later go on to grace the annals of art history as one of the world’s preeminent masters of Impressionism. As a child, Degas received decent grades in both drawing and other academic subjects, but he was often uncommunicative and reportedly lived with his head in the clouds. Given his initial mediocrity, art historians are still mystified about Degas’ early and quick decision to pursue art as a career.

In his teen years, Degas was given permission to sit and sketch the works of masters at the Louvre. The young artist secured a prestigious apprenticeship under Louis Lamotte, and subsequently attended the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Around this time, he also met Neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who gave him a piece of advice that served as a fundamental component of Degas’ artistic process: “Never work from nature, always from memory and the engravings of masters.” Understanding that a proper artistic education and career would require years of hard work and determination, Degas’ approach to his artistic training shifted from haphazard to focused.

Early Career

Degas took Ingres’ advice and spent his early career obsessively rendering the works of Da Vinci and other Renaissance masters. Degas spent years meticulously copying the exact expressions of the artworks created by the great masters, though he was simultaneously not afraid to use his own artistic vision to create differences in form, hue and line. In these formative years abroad, Degas’ creative brilliance emerged. Like Paul Gauguin, who would later move beyond traditional artistic norms, Degas’ ability to reinterpret classical art laid the foundation for his revolutionary style.

Travels to Italy

In 1856, Degas spent time in Italy wherein he put portraiture aside as he explored motifs of historical paintings and local people. His first early masterpiece, Family Portrait, features Degas’ virtuosic ability to capture the intimate relationships between people in a single image. In this painting, the Bellelli family’s complicated relationship is ever-present through the wife’s stern expression and the husband’s tense profile. The two children, innocent though not unobservant, seem aware of the tension. With his Family Portrait, Degas invites his viewer to experience the familial tension, an uncomfortable but intriguing feeling, allowing his viewer the ability to create their own reality of the Bellellis complicated story.

Introduction to Modern Art

In the autumn of 1859, Degas returned to Paris and began experimenting with historical paintings and a new, innovative use of oil paint. With “essence painting,” oil is thinned, dried out and applied to woven paper. The resulting effect, which would later be Degas’ signature technique, brings the oil a unique thickness, brightness and vibrancy.

Throughout the early 1860s, Degas continued to paint with vigor, but his career was at a standstill. This changed when he met Manet, in whom he found a kindred spirit. Manet introduced Degas to modern art, thus inviting him to step away from the historical paintings that had grown frustrating to the artist. It was through this friendship that Degas became an instrumental member of the nascent Impressionist movement, and he began to take creative liberties that distinguished himself as a true revolutionary.

Commercial Success

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Degas had the luxury of his father’s wealth and felt no pressure to sell his paintings. Despite having successful Salon appearances and the respect of his fellow artists, Degas was not commercially successful. This changed when his father died and left the family impecunious. With his eye toward the London and American art markets, Degas found patrons who were both drawn to the Parisian Impressionist movement and taken by Degas’ unique vision.

In this decade of commercial success, Degas discovered a subject that would later encompass most of his oeuvre: ballet dancers. Once given permission to spend time behind the stage, Degas’ dancer paintings allow his viewer to observe from the sidelines as the dances practice, stretch, prepare and perform. Ever true to the Impressionist movement, these scenes catch the dancers in a fleeting moment. The sense of unawareness of the subject — the dancers who often seem oblivious or disinterested in the artists’ gaze — creates an intimate experience of viewership that brought Degas audiences and critical acclaim throughout the world.

New Orleans Visit

In 1872, Degas was persuaded to visit his brother Rene and his American family in New Orleans. Degas was in awe of the city’s riverboats, architecture, music and diversity, but he was strikingly homesick and longed for his cozy Parisian life. Frustrated by America’s “obsession” with industry, after his stay in New Orleans, this would be Degas’ last journey outside of France. For the rest of his life, he only traversed the country from Paris to his vacations at Normandy.

Breaking New Ground

Once back in France, Degas rejoined the artistic community with a renewed sense of purpose and creative vision. In 1874, Degas was at the helm of the revolutionary Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition created by the Société des Artistes Indépendants. The Société was a group of artists joined by a love for the bourgeoning Impressionist artistic philosophy and the belief that they should be able to exhibit their artwork without the impenetrable selection committees. Although these exhibitions were initially met with disdain, the Société persisted, and the Salon des Indépendants would later receive great commercial and critical acclaim.

Throughout the 1880s-90s, though his friendships began to wane, Degas remained the undeniable leader of the Impressionist movement. As Degas grew both older and increasingly private, he would only interact with a few friends and the women and girls who posed for him. Known for his irritable temperament, Degas was grumpy, though not aggressive, and lived his later years increasingly secluded in his large apartment, surrounded by his grand collection of Old Master paintings.

Legacy

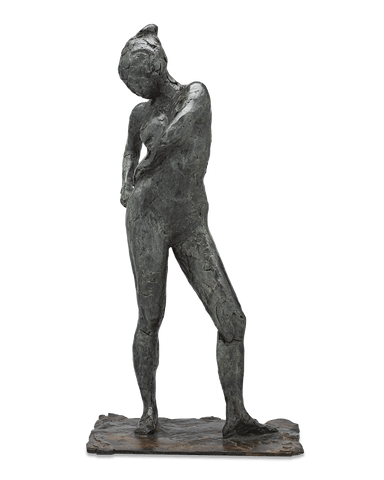

In his old age, Degas continued to reinvent himself as an artist. Through his later sculptural and photography works, Degas moved away from Realism toward Expressionism, creating works that reflect genius experimentations with line and color. Degas’ expansive ever-changing and experimental oeuvre has solidified the master artist as one of the greatest visionaries the world has ever seen.

Quick Facts

Born: July 19, 1834, Paris, France

Death: September 27, 1917, Paris, France

Full Name: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas

Spouse: Never married

Children: No children

5 Most Famous Works:

- L'Absinthe (In a Cafe) (1875 – 76)

- Place de la Concorde (1879)

- The Star (L'Étoile) (1878)

- The Millinery Shop (Chez la modiste) (1879-86)

- After The Bath, Woman Drying Herself (Après le bain, femme s'essuyant) (1895)

Artists & Artisans

Degas, Edgar

Early Life

Born to a wealthy Parisian family, Edgar Degas began his artistic career as an average student; however, he would later go on to grace the annals of art history as one of the world’s preeminent masters of Impressionism. As a child, Degas received decent grades in both drawing and other academic subjects, but he was often uncommunicative and reportedly lived with his head in the clouds. Given his initial mediocrity, art historians are still mystified about Degas’ early and quick decision to pursue art as a career.

In his teen years, Degas was given permission to sit and sketch the works of masters at the Louvre. The young artist secured a prestigious apprenticeship under Louis Lamotte, and subsequently attended the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Around this time, he also met Neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who gave him a piece of advice that served as a fundamental component of Degas’ artistic process: “Never work from nature, always from memory and the engravings of masters.” Understanding that a proper artistic education and career would require years of hard work and determination, Degas’ approach to his artistic training shifted from haphazard to focused.

Early Career

Degas took Ingres’ advice and spent his early career obsessively rendering the works of Da Vinci and other Renaissance masters. Degas spent years meticulously copying the exact expressions of the artworks created by the great masters, though he was simultaneously not afraid to use his own artistic vision to create differences in form, hue and line. In these formative years abroad, Degas’ creative brilliance emerged. Like Paul Gauguin, who would later move beyond traditional artistic norms, Degas’ ability to reinterpret classical art laid the foundation for his revolutionary style.

Travels to Italy

In 1856, Degas spent time in Italy wherein he put portraiture aside as he explored motifs of historical paintings and local people. His first early masterpiece, Family Portrait, features Degas’ virtuosic ability to capture the intimate relationships between people in a single image. In this painting, the Bellelli family’s complicated relationship is ever-present through the wife’s stern expression and the husband’s tense profile. The two children, innocent though not unobservant, seem aware of the tension. With his Family Portrait, Degas invites his viewer to experience the familial tension, an uncomfortable but intriguing feeling, allowing his viewer the ability to create their own reality of the Bellellis complicated story.

Introduction to Modern Art

In the autumn of 1859, Degas returned to Paris and began experimenting with historical paintings and a new, innovative use of oil paint. With “essence painting,” oil is thinned, dried out and applied to woven paper. The resulting effect, which would later be Degas’ signature technique, brings the oil a unique thickness, brightness and vibrancy.

Throughout the early 1860s, Degas continued to paint with vigor, but his career was at a standstill. This changed when he met Manet, in whom he found a kindred spirit. Manet introduced Degas to modern art, thus inviting him to step away from the historical paintings that had grown frustrating to the artist. It was through this friendship that Degas became an instrumental member of the nascent Impressionist movement, and he began to take creative liberties that distinguished himself as a true revolutionary.

Commercial Success

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Degas had the luxury of his father’s wealth and felt no pressure to sell his paintings. Despite having successful Salon appearances and the respect of his fellow artists, Degas was not commercially successful. This changed when his father died and left the family impecunious. With his eye toward the London and American art markets, Degas found patrons who were both drawn to the Parisian Impressionist movement and taken by Degas’ unique vision.

In this decade of commercial success, Degas discovered a subject that would later encompass most of his oeuvre: ballet dancers. Once given permission to spend time behind the stage, Degas’ dancer paintings allow his viewer to observe from the sidelines as the dances practice, stretch, prepare and perform. Ever true to the Impressionist movement, these scenes catch the dancers in a fleeting moment. The sense of unawareness of the subject — the dancers who often seem oblivious or disinterested in the artists’ gaze — creates an intimate experience of viewership that brought Degas audiences and critical acclaim throughout the world.

New Orleans Visit

In 1872, Degas was persuaded to visit his brother Rene and his American family in New Orleans. Degas was in awe of the city’s riverboats, architecture, music and diversity, but he was strikingly homesick and longed for his cozy Parisian life. Frustrated by America’s “obsession” with industry, after his stay in New Orleans, this would be Degas’ last journey outside of France. For the rest of his life, he only traversed the country from Paris to his vacations at Normandy.

Breaking New Ground

Once back in France, Degas rejoined the artistic community with a renewed sense of purpose and creative vision. In 1874, Degas was at the helm of the revolutionary Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition created by the Société des Artistes Indépendants. The Société was a group of artists joined by a love for the bourgeoning Impressionist artistic philosophy and the belief that they should be able to exhibit their artwork without the impenetrable selection committees. Although these exhibitions were initially met with disdain, the Société persisted, and the Salon des Indépendants would later receive great commercial and critical acclaim.

Throughout the 1880s-90s, though his friendships began to wane, Degas remained the undeniable leader of the Impressionist movement. As Degas grew both older and increasingly private, he would only interact with a few friends and the women and girls who posed for him. Known for his irritable temperament, Degas was grumpy, though not aggressive, and lived his later years increasingly secluded in his large apartment, surrounded by his grand collection of Old Master paintings.

Legacy

In his old age, Degas continued to reinvent himself as an artist. Through his later sculptural and photography works, Degas moved away from Realism toward Expressionism, creating works that reflect genius experimentations with line and color. Degas’ expansive ever-changing and experimental oeuvre has solidified the master artist as one of the greatest visionaries the world has ever seen.

Quick Facts

Born: July 19, 1834, Paris, France

Death: September 27, 1917, Paris, France

Full Name: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas

Spouse: Never married

Children: No children

5 Most Famous Works:

- L'Absinthe (In a Cafe) (1875 – 76)

- Place de la Concorde (1879)

- The Star (L'Étoile) (1878)

- The Millinery Shop (Chez la modiste) (1879-86)

- After The Bath, Woman Drying Herself (Après le bain, femme s'essuyant) (1895)