Artists & Artisans

Cassatt, Mary

“I have touched with a sense of art some people— they felt the love and the life. Can you offer me anything to compare to that joy for an artist?” - Mary Cassatt

| Mother Holding a Baby Playing with a Toy Duck by Cassatt. 1914. Oil on canvas. M.S. Rau (sold). |

Known for her poignant portrayals of mothers and children, Mary Cassatt is a pivotal figure in the French Impressionist movement. Her work not only captures the essence of familial bonds but also greatly challenges the norms of her time. Cassatt broke away from her home country and the conventional paths of marriage and motherhood to carve out a distinguished career as an artist in the late 19th- and 20th-century male-dominated world. While her portraits may seem demure in the twenty-first century, Cassatt championed the prioritization of depicting women’s lives in art while eschewing the common male gaze. Through her exceptional talent, pioneering spirit and independent voice, Cassatt earned her place as an enduring icon in both American and European art history.

Early Years and Artistic Beginnings |

Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, on May 22, 1844. Cassatt, the daughter of a successful stockbroker and land speculator, grew up in a well-to-do upper-middle-class family. Her mother, Katherine Kelso Johnston Cassatt, heavily prioritized a proper education for her children, so Mary was taught to be well-read, learned German and French and took drawing and painting lessons. Her parents also viewed travel as integral to education, so Cassatt spent five years abroad in Europe, where she was exposed first-hand to the Old Masters.

|

Mary Cassatt by Alphone J. Liébert & Co. Circa 1867. Photograph. Private Collection.

|

It came as an unwelcome surprise to Cassatt’s parents that she was determined at a young age to make a career as an artist. At age 15, in 1861, Cassatt began studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. Her family vehemently rejected her aspirations, citing the exposure to feminist ideas and the “bohemian” manners of the young men as impropriety for their daughter. In fact, about 20% of PAFA’s student population was female, though most attended to hone their skills for socially valuable reasons, not with the same aspirations as Cassatt.

While PAFA was a good start for honing her craft, Cassatt decided to leave the academy after four years due to the slow pace of instruction, which forbade female students from drawing after live models, and the misogynistic behavior of her male counterparts. Looking back at this early education, Cassatt later said, “There was no teaching [at the academy]."

Journey to Paris: Embracing the French Art Scene |

In 1866, after overcoming her father’s objections, Cassatt set sail for Paris with her mother and family friends in tow as chaperones. Due to the prohibition of women as students at the École des Beaux-Arts, Cassatt took up private lessons with Jean-Léon Gérôme, a teacher highly regarded at the École for his penchant for hyperrealism. To supplement her lessons, Cassatt also began copying Old Masters at the Louvre.

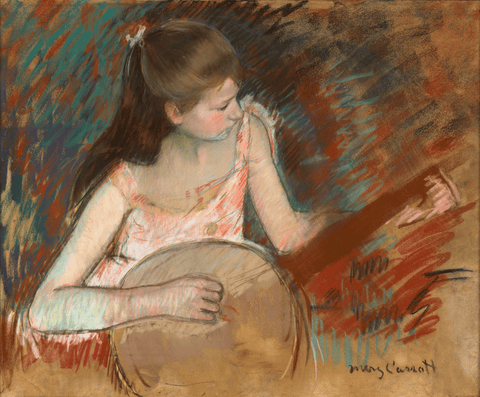

| The Mandolin Player by Cassatt. 1868. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. |

Two years into her stay, Cassatt’s painting The Mandolin Player (1868) was accepted for exhibition at the Paris Salon. The work, painted in the Romantic style, reflects her traditional arts education and hours spent studying the techniques of the Old Masters. While Cassatt finally felt a professional career in art was upon her, the Franco-Prussian War dashed her efforts.

A Brief Sojourn Home |

When the Franco-Prussian War began in 1870, the American artist returned to the United States and to her family’s home. The abrupt move, coupled with the reintegration into a family who did not support her endeavors, temporarily dashed her dreams of the future. Her father refused to pay for her art supplies, and when she briefly moved to Chicago to attempt to find a market for her work, she lost many paintings in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. In a letter from that period, she wrote, “I have given up my studio and torn up my father’s portrait, and have not touched a brush for six weeks nor will I ever again until I see some prospect of getting back to Europe.”

|

Bacchante by Cassatt. 1872. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania.

|

Luckily for her, Cassatt's paintings drew the attention of Roman Catholic Bishop Michael Domenec. He decided to commission her to paint two copies of Correggio paintings in Parma, Italy and paid for her travel expenses. In 1872, Cassatt was back in Europe, where she successfully completed the commission and found an audience for her works in Parma, so much so that she was able to extend her travels into Madrid and Seville, Spain. Hitting her stride, she was accepted to exhibit works in the Paris Salon four times between 1872 and 1876.

Finding Her Style: Impressionism and the Influence of Edgar Degas |

In the midst of her newfound successes, in 1874, Cassatt decided to return to Paris and permanently reside in France. Although she was exhibiting in the Salons, she was outspoken in her criticisms of the conventional traditions preferred by the jurors. She felt stifled by the Academic style but continued to paint genre paintings in order to maintain her customer base. In 1877, her entries to the Salon were rejected for the first time in seven years, and she felt her career was slipping.

|

The Reader by Cassatt. 1877. Oil on canvas. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

|

Coincidentally, that same year, she began a friendship with Edgar Degas, who exposed her to the world of art outside of the Academic traditions. Already an admirer of Degas, Cassatt reminisced on seeing his work in 1875, saying, “I used to go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art. It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it.”

Degas encouraged Cassatt to experiment with new techniques, perspectives, compositions and the use of light and color. Under his tutelage, Cassatt began using pastels, which became a significant portion of her oeuvre. She also inherited Degas’ interest in capturing everyday life with authenticity and sensitivity, though she was unable to sit at the cafés frequented by Degas due to the unwanted negative attention it would attract. Instead, Cassatt met with Degas and other Impressionists in private and began carrying a sketchbook with her wherever she went, including the theater where her iconic painting In the Loge (1878) is based.

|

In the Loge by Cassatt. 1878. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

In 1879, Cassatt joined the Impressionist exhibition at Degas’ invitation, the only American painter to ever do so. She contributed to their shows three times afterward, never again joining the Paris Salon for the rest of her career. During this time, she also met fellow female Impressionist artist, Berthe Morisot. Both women artists eventually stamped their legacy in the Impressionist movement and modern art.

Impressionist Triumphs and Artistic Evolution |

| Susan Comforting the Baby, no. 1 by Cassatt. Circa 1881. Oil on canvas. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. |

In 1880, Cassatt’s nephews and nieces arrived in France. The company of her young relations with their mothers is one of the most prominent reasons that inspired Cassatt to turn her attention to women and children. Although Cassatt chose never to marry and, instead, focused all her attention on her career, her relegation to private, domestic spaces as a single woman developed a keen understanding of the mother and child relationship. Through portraits of mothers, children and young, modern women in private settings, she was able to elevate the subject matter of women’s lives and domestic spaces without infusing the scenes with excessive sentimentality. Cassatt championed the importance of the subject matter and its dignity in the realm of fine art, which led to her commercial success.

The 1880s and 1890s were Cassatt’s busiest and most creative periods. In these decades, Cassatt experimented heavily with new forms of media, including mastering her printmaking techniques in Degas’ print studio. In 1891, Cassatt exhibited a series of colored drypoint and aquatint prints heavily inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e prints that were shown in Paris the year before. The prints are pared down to simplistic background designs, and Cassatt employed primarily delicate pastel colors to draw the viewer’s eye into the scene. Adelyn D. Breeksin, the author of two of Cassatt’s catalogue raisonnés, calls this body of work “her most original contribution... adding a new chapter to the history of graphic arts.”

|

In the Omnibus by Cassatt. 1890-1891. Drypoint and aquatint on laid paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

|

Later Career and Suffragist Efforts |

In the early 20th century, Cassatt’s works were ingrained into popularity with the public and critics. Knowing her target audience, Cassatt honed in on her portraits of domestic interiors, which she continued to produce extensively until 1910. In 1904, France awarded her the Légion d’honneur for her immense contributions to the arts.

| Sara in a Round-Brimmed Bonnet, Holding her Dog by Cassatt. Circa 1901. Pastel on paper. M.S. Rau. |

In 1911, Cassatt was diagnosed with a milieu of health complications, including diabetes and cataracts. Although she continued to paint, she ultimately had to put down her paintbrush after going almost entirely blind in 1914. After this forced retirement, Cassatt pivoted and began serving as an advisor to American collectors who were interested in purchasing Impressionist artworks, though she stipulated that they must donate works to American art museums if she worked with them. Although her recognition in America did not begin until the last decade of her career, with two of her works shown in the iconic 1913 Armory show in New York, her efforts in bringing French Impressionism to the United States greatly impacted the love for Impressionism that would be adopted by many Americans.

In 1915, Louisine Havermeyer, a female collector who was among the first to collect French Impressionism in America, thanks to the advice of Cassatt, put together a joint exhibition in 1915 of Degas and Cassatt’s works. Louisine was a dedicated suffragist, and she used the exhibition of her art collection at the Knoedler Gallery to fundraise for suffrage efforts. Cassatt was a fierce advocate for women’s rights all her life, and she was quick to lend works for Louisine’s exhibition.

| Woman with a Sunflower by Cassatt. Shown at the Havemeyer Exhibition, Knoedler Gallery, 1915. Circa 1905. Oil on Canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

However, Cassatt’s family in Philadelphia were noted anti-suffragists, and they refused to loan early works by the artist to the 1915 exhibition despite Cassatt’s wishes. This decision, after decades of fighting against the traditionalist views of her family to pursue her dream life, angered and disappointed Cassatt. Thus, instead of leaving some of her most treasured works to her nieces and nephews in her will, she sold the works to major museums in America and France.

The exhibition was a massive success despite the lack of early works by Cassatt. With the revenue raised from ticket and exhibition brochure sales, Louisine was able to found the Women Suffrage Campaign Fund. Cassatt wrote afterward to her cherished friend and client, “My dear, I am so very glad about the exhibition . . . you deserve all the credit. . . . The time has finally come to show that women can do something.”

Legacy |

Cassatt died on June 14, 1926, and was buried with her family in Le Mesnil-Théribus, France. Cassatt’s legacy as one of the few female artists in a male-dominated world who chose to pursue a career over marriage and children is both inspiring and heartbreaking. In her time, Cassatt felt there was no room for being both a mother and an artist. Cassatt made countless sacrifices for her dream and, in doing so, inspired generations of artists, particularly women, to pursue their creative visions. In 1973, almost fifty years after her death, she was posthumously inducted into the United States National Women’s Hall of Fame.

| Mary Cassatt by Edgar Degas. Circa 1880-1884. Oil on Canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. |

Her focus on intimate domestic scenes and the tender relationship between mothers and children brought a unique perspective to Impressionism, highlighting the beauty and importance of everyday life. Cassatt's technique, characterized by delicate brushwork and innovative use of color and light, set her apart and earned her a place among the great artists of her time. Today, her paintings are celebrated in major museums around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art, ensuring her contributions to art history are recognized and appreciated by audiences and scholars alike. M.S. Rau proudly offers a curated selection of original Mary Cassatt art for collectors. For more details, please contact us today.

Artists & Artisans

Cassatt, Mary

“I have touched with a sense of art some people— they felt the love and the life. Can you offer me anything to compare to that joy for an artist?” - Mary Cassatt

| Mother Holding a Baby Playing with a Toy Duck by Cassatt. 1914. Oil on canvas. M.S. Rau (sold). |

Known for her poignant portrayals of mothers and children, Mary Cassatt is a pivotal figure in the French Impressionist movement. Her work not only captures the essence of familial bonds but also greatly challenges the norms of her time. Cassatt broke away from her home country and the conventional paths of marriage and motherhood to carve out a distinguished career as an artist in the late 19th- and 20th-century male-dominated world. While her portraits may seem demure in the twenty-first century, Cassatt championed the prioritization of depicting women’s lives in art while eschewing the common male gaze. Through her exceptional talent, pioneering spirit and independent voice, Cassatt earned her place as an enduring icon in both American and European art history.

Early Years and Artistic Beginnings |

Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, on May 22, 1844. Cassatt, the daughter of a successful stockbroker and land speculator, grew up in a well-to-do upper-middle-class family. Her mother, Katherine Kelso Johnston Cassatt, heavily prioritized a proper education for her children, so Mary was taught to be well-read, learned German and French and took drawing and painting lessons. Her parents also viewed travel as integral to education, so Cassatt spent five years abroad in Europe, where she was exposed first-hand to the Old Masters.

|

Mary Cassatt by Alphone J. Liébert & Co. Circa 1867. Photograph. Private Collection.

|

It came as an unwelcome surprise to Cassatt’s parents that she was determined at a young age to make a career as an artist. At age 15, in 1861, Cassatt began studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. Her family vehemently rejected her aspirations, citing the exposure to feminist ideas and the “bohemian” manners of the young men as impropriety for their daughter. In fact, about 20% of PAFA’s student population was female, though most attended to hone their skills for socially valuable reasons, not with the same aspirations as Cassatt.

While PAFA was a good start for honing her craft, Cassatt decided to leave the academy after four years due to the slow pace of instruction, which forbade female students from drawing after live models, and the misogynistic behavior of her male counterparts. Looking back at this early education, Cassatt later said, “There was no teaching [at the academy]."

Journey to Paris: Embracing the French Art Scene |

In 1866, after overcoming her father’s objections, Cassatt set sail for Paris with her mother and family friends in tow as chaperones. Due to the prohibition of women as students at the École des Beaux-Arts, Cassatt took up private lessons with Jean-Léon Gérôme, a teacher highly regarded at the École for his penchant for hyperrealism. To supplement her lessons, Cassatt also began copying Old Masters at the Louvre.

| The Mandolin Player by Cassatt. 1868. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. |

Two years into her stay, Cassatt’s painting The Mandolin Player (1868) was accepted for exhibition at the Paris Salon. The work, painted in the Romantic style, reflects her traditional arts education and hours spent studying the techniques of the Old Masters. While Cassatt finally felt a professional career in art was upon her, the Franco-Prussian War dashed her efforts.

A Brief Sojourn Home |

When the Franco-Prussian War began in 1870, the American artist returned to the United States and to her family’s home. The abrupt move, coupled with the reintegration into a family who did not support her endeavors, temporarily dashed her dreams of the future. Her father refused to pay for her art supplies, and when she briefly moved to Chicago to attempt to find a market for her work, she lost many paintings in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. In a letter from that period, she wrote, “I have given up my studio and torn up my father’s portrait, and have not touched a brush for six weeks nor will I ever again until I see some prospect of getting back to Europe.”

|

Bacchante by Cassatt. 1872. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania.

|

Luckily for her, Cassatt's paintings drew the attention of Roman Catholic Bishop Michael Domenec. He decided to commission her to paint two copies of Correggio paintings in Parma, Italy and paid for her travel expenses. In 1872, Cassatt was back in Europe, where she successfully completed the commission and found an audience for her works in Parma, so much so that she was able to extend her travels into Madrid and Seville, Spain. Hitting her stride, she was accepted to exhibit works in the Paris Salon four times between 1872 and 1876.

Finding Her Style: Impressionism and the Influence of Edgar Degas |

In the midst of her newfound successes, in 1874, Cassatt decided to return to Paris and permanently reside in France. Although she was exhibiting in the Salons, she was outspoken in her criticisms of the conventional traditions preferred by the jurors. She felt stifled by the Academic style but continued to paint genre paintings in order to maintain her customer base. In 1877, her entries to the Salon were rejected for the first time in seven years, and she felt her career was slipping.

|

The Reader by Cassatt. 1877. Oil on canvas. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

|

Coincidentally, that same year, she began a friendship with Edgar Degas, who exposed her to the world of art outside of the Academic traditions. Already an admirer of Degas, Cassatt reminisced on seeing his work in 1875, saying, “I used to go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art. It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it.”

Degas encouraged Cassatt to experiment with new techniques, perspectives, compositions and the use of light and color. Under his tutelage, Cassatt began using pastels, which became a significant portion of her oeuvre. She also inherited Degas’ interest in capturing everyday life with authenticity and sensitivity, though she was unable to sit at the cafés frequented by Degas due to the unwanted negative attention it would attract. Instead, Cassatt met with Degas and other Impressionists in private and began carrying a sketchbook with her wherever she went, including the theater where her iconic painting In the Loge (1878) is based.

|

In the Loge by Cassatt. 1878. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

In 1879, Cassatt joined the Impressionist exhibition at Degas’ invitation, the only American painter to ever do so. She contributed to their shows three times afterward, never again joining the Paris Salon for the rest of her career. During this time, she also met fellow female Impressionist artist, Berthe Morisot. Both women artists eventually stamped their legacy in the Impressionist movement and modern art.

Impressionist Triumphs and Artistic Evolution |

| Susan Comforting the Baby, no. 1 by Cassatt. Circa 1881. Oil on canvas. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. |

In 1880, Cassatt’s nephews and nieces arrived in France. The company of her young relations with their mothers is one of the most prominent reasons that inspired Cassatt to turn her attention to women and children. Although Cassatt chose never to marry and, instead, focused all her attention on her career, her relegation to private, domestic spaces as a single woman developed a keen understanding of the mother and child relationship. Through portraits of mothers, children and young, modern women in private settings, she was able to elevate the subject matter of women’s lives and domestic spaces without infusing the scenes with excessive sentimentality. Cassatt championed the importance of the subject matter and its dignity in the realm of fine art, which led to her commercial success.

The 1880s and 1890s were Cassatt’s busiest and most creative periods. In these decades, Cassatt experimented heavily with new forms of media, including mastering her printmaking techniques in Degas’ print studio. In 1891, Cassatt exhibited a series of colored drypoint and aquatint prints heavily inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e prints that were shown in Paris the year before. The prints are pared down to simplistic background designs, and Cassatt employed primarily delicate pastel colors to draw the viewer’s eye into the scene. Adelyn D. Breeksin, the author of two of Cassatt’s catalogue raisonnés, calls this body of work “her most original contribution... adding a new chapter to the history of graphic arts.”

|

In the Omnibus by Cassatt. 1890-1891. Drypoint and aquatint on laid paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

|

Later Career and Suffragist Efforts |

In the early 20th century, Cassatt’s works were ingrained into popularity with the public and critics. Knowing her target audience, Cassatt honed in on her portraits of domestic interiors, which she continued to produce extensively until 1910. In 1904, France awarded her the Légion d’honneur for her immense contributions to the arts.

| Sara in a Round-Brimmed Bonnet, Holding her Dog by Cassatt. Circa 1901. Pastel on paper. M.S. Rau. |

In 1911, Cassatt was diagnosed with a milieu of health complications, including diabetes and cataracts. Although she continued to paint, she ultimately had to put down her paintbrush after going almost entirely blind in 1914. After this forced retirement, Cassatt pivoted and began serving as an advisor to American collectors who were interested in purchasing Impressionist artworks, though she stipulated that they must donate works to American art museums if she worked with them. Although her recognition in America did not begin until the last decade of her career, with two of her works shown in the iconic 1913 Armory show in New York, her efforts in bringing French Impressionism to the United States greatly impacted the love for Impressionism that would be adopted by many Americans.

In 1915, Louisine Havermeyer, a female collector who was among the first to collect French Impressionism in America, thanks to the advice of Cassatt, put together a joint exhibition in 1915 of Degas and Cassatt’s works. Louisine was a dedicated suffragist, and she used the exhibition of her art collection at the Knoedler Gallery to fundraise for suffrage efforts. Cassatt was a fierce advocate for women’s rights all her life, and she was quick to lend works for Louisine’s exhibition.

| Woman with a Sunflower by Cassatt. Shown at the Havemeyer Exhibition, Knoedler Gallery, 1915. Circa 1905. Oil on Canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

However, Cassatt’s family in Philadelphia were noted anti-suffragists, and they refused to loan early works by the artist to the 1915 exhibition despite Cassatt’s wishes. This decision, after decades of fighting against the traditionalist views of her family to pursue her dream life, angered and disappointed Cassatt. Thus, instead of leaving some of her most treasured works to her nieces and nephews in her will, she sold the works to major museums in America and France.

The exhibition was a massive success despite the lack of early works by Cassatt. With the revenue raised from ticket and exhibition brochure sales, Louisine was able to found the Women Suffrage Campaign Fund. Cassatt wrote afterward to her cherished friend and client, “My dear, I am so very glad about the exhibition . . . you deserve all the credit. . . . The time has finally come to show that women can do something.”

Legacy |

Cassatt died on June 14, 1926, and was buried with her family in Le Mesnil-Théribus, France. Cassatt’s legacy as one of the few female artists in a male-dominated world who chose to pursue a career over marriage and children is both inspiring and heartbreaking. In her time, Cassatt felt there was no room for being both a mother and an artist. Cassatt made countless sacrifices for her dream and, in doing so, inspired generations of artists, particularly women, to pursue their creative visions. In 1973, almost fifty years after her death, she was posthumously inducted into the United States National Women’s Hall of Fame.

| Mary Cassatt by Edgar Degas. Circa 1880-1884. Oil on Canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. |

Her focus on intimate domestic scenes and the tender relationship between mothers and children brought a unique perspective to Impressionism, highlighting the beauty and importance of everyday life. Cassatt's technique, characterized by delicate brushwork and innovative use of color and light, set her apart and earned her a place among the great artists of her time. Today, her paintings are celebrated in major museums around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art, ensuring her contributions to art history are recognized and appreciated by audiences and scholars alike. M.S. Rau proudly offers a curated selection of original Mary Cassatt art for collectors. For more details, please contact us today.