Artists & Artisans

Chagall, Marc

Introduction:

One of the most influential painters of the twentieth century, Marc Chagall defied the expectations of the century's art movements. His poetic, expressive work could not be limited to one genre— he moved in and out of Cubism, Fauvism and Surrealism in his search to define the relationship between abstraction and figurative art. Throughout his 75-year career, in which he produced over 10,000 artworks, Chagall created a dreamy, pictorial universe reflecting his journey as an emigrated Jew, a lover and a man dedicated to color. As essayist Clement Greenberg aptly said in 1946, “Some become painters by controlling or deflecting their gifts- and even attain greatness- but Chagall was born into paint, into the canvas, into the picture, with his clumsiness and all.”

Personal Background:

Marc Chagall, née Moyshe (Moshe) Shegal, was born on July 7, 1887, in the Belorussian town of Liozna, near Vitebsk. Born into an Orthodox Jewish family, he was the eldest of nine siblings and was expected to help support his family. His father, Khatskl-Mordechai, worked in a herring warehouse, whereas his mother, Feiga-Ita Chernina, ran a small grocery business out of the family home. Growing up in a Hasidic Jewish household at the turn of the twentieth century meant Chagall experienced much religious discrimination. During one pogrom, a common event in Eastern European Jewish villages where a violent riot of people attacked Jews, Chagall had to hide his Jewish identity to survive. As a boy, he wrote, “I felt at every step that I was a Jew—people made me feel it.” This discrimination, coupled with growing up in a highly observant household defined by prayer, inspired Chagall to embrace his religious background as the basis of his artistic creation.

Chagall was first exposed to art in high school when he noticed a nearby student drawing. There was no art in his household, and the concept of artistic creation was utterly foreign to him. His parents’ observance of Hasidic Jewish forbade the graphic representation of anything created by God. When Chagall, in his late teens, began studying under a local Jewish artist in Vitebsk, a pious uncle refused to shake his hand. While Chagall remained committed to a vision of himself as an artist, he was unsatisfied with his education in Vitebsk. The academic portrait painting school did not suit the type of art Chagall wanted to make, so he left his family's quaint village and embarked on a journey to find a more suitable arts education.

Career Overview:

The Early Years: St. Petersburg (1906-1910)

In 1906, at age 19, Chagall moved to St. Petersburg, the capital of Russia's artistic life, using a temporary passport that bypassed the restriction on Jews entering the city without an internal passport. There, he began studying at the prestigious Imperial Society for the Protection of Fine Arts. He participated in classical arts training for two years, where he primarily painted naturalistic landscapes and self-portraits. Though successful, he found the world of classical arts stifling. In 1908, he switched to studying under Léon Bakst at the Zvantseva School of Painting, where the young artist found support for his expressive, unconventional approach to figurative art. Bakst, who had spent time in Paris, rubbing shoulders with artists like Matisse, Cezanne and Manet, introduced Chagall to the world of modern art and the idea that artists could define their artistic style. While this art period is not his most well-known, this formative early experience in St. Petersburg inspired his colorful style, unashamed sentimentality and sense of humor.

The First Introduction to Paris (1910-1914)

In 1911, due to a stipend from a member of the Duma, Russia's assembly, who took a liking to the artist, Chagall moved to Paris at age 23. This period is considered by many to be his most boldly creative and experimentative, as he experimented with the various artistic styles popular in France. He found a room in the artist's commune La Ruche in Montmartre, where he met other painters like Fernand Léger, Chaim Soutine, and Amedeo Modigliani. At the time of his arrival, Cubism was trending heavily with the output of Braque's and Picasso's abstract paintings. Chagall married the geometric aspect of Cubism with the more colorful and playful Fauvism, such as the Cubist-influenced Temptation (Adam and Eve). The early years in Paris coincided with Chagall's courtship of his first wife, Bella Rosenfeld, whom he loved fiercely and provided much inspiration for his early experimental work. He said later, “Even in my twenties, I preferred dreaming about love and painting it in my pictures.” One can imagine this love inspired him to make Dedicated to My Fiancée, an explosive painting he completed feverishly in a single night before submitting it to a major Paris exhibition.

World War I and a Return to Russia (1914-1922)

In 1914, Chagall traveled to Berlin for a major exhibition of his work at the Sturm Gallery, where he brought 40 canvases and 160 gouaches and watercolors. After the successful exhibition, Chagall returned to Vitebsk, only planning on staying enough time to marry Bella and bring her back to France. Unfortunately, World War I broke out not long after his arrival, closing the Russian border indefinitely. This period is characterized by Chagall's musings on love and marriage, painting many scenes of the happy couple transcending borders, a real-life impossibility for them at the time. Art historian Michael J. Lewis aptly wrote of this period, “[T]he euphoric paintings of this time, which show the young couple floating balloon-like over Vitebsk- its wooden building faceted in the Delaunay manner- are the most lighthearted of his career.” This is also when, Chagall began exhibiting in Russia, first in Moscow in 1915 and then at a salon in St. Petersburg in 1916. By the October Revolution in 1917, Chagall had become a well-known artist and a member of the modernist avant-garde movement, which granted him special privileges as the ‘aesthetic arm of the revolution.’ Thus, he became a commissar of arts in Vitebsk, where he founded the Vitebsk People’s Arts School, the most distinguished school of art in the Soviet Union.

Although Chagall enjoyed success with his painting, he lived meagerly in Vitebsk and on the outskirts of Moscow with his wife and young daughter, Ida. Chagall took illustration jobs to make ends meet, where he made ink drawings for several Yiddish books. In 1921, he worked as an art teacher at a Jewish boys’ shelter for young children who lost their parents due to pogroms. Chagall designed the set for the new State Jewish Chamber Theater in Moscow in the same year. The large-scale background murals included a variety of motifs that would become staples to his oeuvre, such as fiddlers, acrobats, farm animals and dancers. The murals, which read like a dictionary of Chagall's symbols, were the forerunners of his later murals at the New York and Paris Metropolitan Operas. After tiring of the primitive living conditions and worsening famine, Chagall obtained an exit visa and moved his family back to Paris in 1923.

The Inter-War Period (1923-1941)

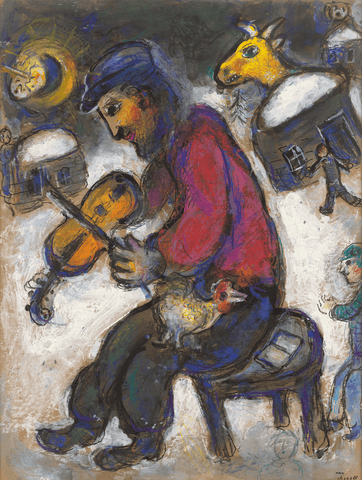

Before arriving in France, Chagall stopped in Berlin to try to recover the paintings he had left there before the outbreak of war, which were all lost or unrecoverable. This loss of so much of his early work pushed Chagall to reimagine his memories of Vitebsk through new works of art. Demonstrating his Belarusian Jewish origin, Chagall painted fervently, producing a massive body of work reflecting life with a childlike sensibility mixed with romantic highlights and a hint of sadness about what had been lost or left behind. The Green Violinist from 1923-24 stems from his memories of the Russian countryside in his Jewish hometown, recalling a communion of God through dancing and music. His many illustrations of fiddlers inspired the name of the 1964 musical, Fiddler on the Roof.

At this time, Chagall formed a critical business relationship with Ambroise Vollard, a well-known French art dealer. Vollard commissioned Chagall to illustrate the La Fontaine Fables (1928-31) and the Bible (1931-40). The biblical illustrations were an excuse for Chagall to travel to Mandatory Palestine, visiting Christian and Jewish religious sites, such as the Western Wall and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The trip fascinated Chagall, and he felt a kinship with the many people who spoke Yiddish and Russian, prompting him to stay for two months. Chagall reminisced on the trip that Israel gave him “the most vivid impression I have ever seen” and that “In the East I found the Bible and part of my own being.” From this point forward, the Old Testament and Bible became primary inspirations Chagall drew from, working obsessively to recreate an air of the whimsical religiosity and self-reflection he experienced in the Holy Land. These motifs inspired one of his most well-known works, the White Crucifixion.

In 1938, at the age of 51, Chagall painted a crucified Christ, covered in a white prayer shawl, as a symbol of the suffering of all Jews. In the face of Adolf Hitler and the growing Nazi movement, Chagall called out the injustices being committed to European Jewry, painting the burning synagogues and emigrants fleeing that was playing out on the other side of Europe. At this time, Chagall's paintings were facing major criticism in Nazi Germany for degeneracy, leading to more destruction of his artwork. Not long after, the Vichy puppet government began in 1940, waking Chagall up to the danger his family would face. Chagall and his family escaped to the South of France, where his inclusion on a list of prominent artists whose lives were at risk prompted the United States to extricate him. Thus, in 1941, Chagall was stripped of his French citizenship and moved to New York City.

A Brief Stint in the United States (1941-48)

At 54 years old, Chagall found himself in a new country, attempting to learn a new language and among a new artistic community with different priorities than himself. The European conflict emboldened Chagall's folklorist commitment to Russo-Jewish imagery and mysticism, reflecting on his relationship with emigration. Chagall found a sense of homeliness in the many Jewish communities in New York City, where he could read a Yiddish newspaper for news and enjoy Jewish foods. This period is marked by its darkened palette and tragic imagery, much like the 1945 painting About Her.

The news of the destruction of Vitebsk and Nazi concentration camps, coupled with the sudden death of his beloved wife Bella in 1944 to a viral infection, rocked Chagall's world, where he stated, “Everything turned black.” The months after Bella's death were the most silent in Chagall's artistic production. When he did return to painting, the practice focused on preserving Bella's memory along with the many Jewish lives lost in Europe.

As the war wound down and the Allies liberated France, Chagall longed to return to Paris. He reflected on his ambivalent time in America, “I know I must live in France, but I don't want to cut myself off from America. France is a picture already painted. America still has to be painted. Maybe that's why I feel freer there. But when I work in America, it's like shouting in a forest. There's no echo.” Thus in 1948, Chagall resettled in France, where he would stay for the rest of his life. One of his other notable works during this time was his paintings on the ceiling of the Paris Opéra House. Commissioned by Minister of Culture André Malraux in 1964, the nearly 2,600-square-foot canvas stands out for its vibrant colors paying homage to major composers and portraying notable Parisian monuments.

Legacy and Later Life:

Compared to Chagall's earlier periods, the works Chagall produced in the latter part of his career were more melancholy in both subject and color, as well as more abstract in form. Chagall returned to the same motifs of the Russo-Jewish countryside, reimagining the Europe of his youth that was now lost. He also maintained the use of vibrant color, even if paired with a darker background, such as his 1973 work Mère et enfant sur l’âne marron. This is visible in Musicians sur fond Multicolore, a masterpiece that offers a captivating glimpse into the artist's most cherished motifs.

It was in the twilight of his life that Chagall also began experimenting with other mediums. Most notably, this period is marked by the creation of stained-glass windows, starting in 1956 at age 70. These windows enhanced the effect of light on Chagall's colorful works. They decorated the walls of cathedrals and synagogues in Europe and America, including a work entitled Peace for the United Nations building.

When he passed away in 1985, at 97, Chagall was still actively painting and working in other mediums. Always the avant-garde artist who stayed true to his folk roots, Chagall pioneered modern art and was one of the greatest figurative painters of the 20th century. In the face of a life filled with discrimination against Judaism, emigration, and the loss of his great loves, Chagall made a breakthrough in self-expression through art. He distilled his identity, fondest memories and sadness into his paintings, creating an other-worldly symbolic landscape that any viewer could respond to. His tranquil figures and enigmatic colors produced a sense of monumentality, reimagining Jewish cultural motifs and values that had been long ignored in painting. French novelist and art theorist André Malraux said it best: “[Chagall] is the greatest image-maker of this century. He has looked at our world with the light of freedom and seen it with the colours of love.”

Today, Chagall’s work is highly sought after by collectors. His distinctive style and vibrant colors have made him a key figure in modern art. M.S. Rau proudly offers a curated selection of Marc Chagall original paintings for sale. For more information, please contact us today.

Artists & Artisans

Chagall, Marc

Introduction:

One of the most influential painters of the twentieth century, Marc Chagall defied the expectations of the century's art movements. His poetic, expressive work could not be limited to one genre— he moved in and out of Cubism, Fauvism and Surrealism in his search to define the relationship between abstraction and figurative art. Throughout his 75-year career, in which he produced over 10,000 artworks, Chagall created a dreamy, pictorial universe reflecting his journey as an emigrated Jew, a lover and a man dedicated to color. As essayist Clement Greenberg aptly said in 1946, “Some become painters by controlling or deflecting their gifts- and even attain greatness- but Chagall was born into paint, into the canvas, into the picture, with his clumsiness and all.”

Personal Background:

Marc Chagall, née Moyshe (Moshe) Shegal, was born on July 7, 1887, in the Belorussian town of Liozna, near Vitebsk. Born into an Orthodox Jewish family, he was the eldest of nine siblings and was expected to help support his family. His father, Khatskl-Mordechai, worked in a herring warehouse, whereas his mother, Feiga-Ita Chernina, ran a small grocery business out of the family home. Growing up in a Hasidic Jewish household at the turn of the twentieth century meant Chagall experienced much religious discrimination. During one pogrom, a common event in Eastern European Jewish villages where a violent riot of people attacked Jews, Chagall had to hide his Jewish identity to survive. As a boy, he wrote, “I felt at every step that I was a Jew—people made me feel it.” This discrimination, coupled with growing up in a highly observant household defined by prayer, inspired Chagall to embrace his religious background as the basis of his artistic creation.

Chagall was first exposed to art in high school when he noticed a nearby student drawing. There was no art in his household, and the concept of artistic creation was utterly foreign to him. His parents’ observance of Hasidic Jewish forbade the graphic representation of anything created by God. When Chagall, in his late teens, began studying under a local Jewish artist in Vitebsk, a pious uncle refused to shake his hand. While Chagall remained committed to a vision of himself as an artist, he was unsatisfied with his education in Vitebsk. The academic portrait painting school did not suit the type of art Chagall wanted to make, so he left his family's quaint village and embarked on a journey to find a more suitable arts education.

Career Overview:

The Early Years: St. Petersburg (1906-1910)

In 1906, at age 19, Chagall moved to St. Petersburg, the capital of Russia's artistic life, using a temporary passport that bypassed the restriction on Jews entering the city without an internal passport. There, he began studying at the prestigious Imperial Society for the Protection of Fine Arts. He participated in classical arts training for two years, where he primarily painted naturalistic landscapes and self-portraits. Though successful, he found the world of classical arts stifling. In 1908, he switched to studying under Léon Bakst at the Zvantseva School of Painting, where the young artist found support for his expressive, unconventional approach to figurative art. Bakst, who had spent time in Paris, rubbing shoulders with artists like Matisse, Cezanne and Manet, introduced Chagall to the world of modern art and the idea that artists could define their artistic style. While this art period is not his most well-known, this formative early experience in St. Petersburg inspired his colorful style, unashamed sentimentality and sense of humor.

The First Introduction to Paris (1910-1914)

In 1911, due to a stipend from a member of the Duma, Russia's assembly, who took a liking to the artist, Chagall moved to Paris at age 23. This period is considered by many to be his most boldly creative and experimentative, as he experimented with the various artistic styles popular in France. He found a room in the artist's commune La Ruche in Montmartre, where he met other painters like Fernand Léger, Chaim Soutine, and Amedeo Modigliani. At the time of his arrival, Cubism was trending heavily with the output of Braque's and Picasso's abstract paintings. Chagall married the geometric aspect of Cubism with the more colorful and playful Fauvism, such as the Cubist-influenced Temptation (Adam and Eve). The early years in Paris coincided with Chagall's courtship of his first wife, Bella Rosenfeld, whom he loved fiercely and provided much inspiration for his early experimental work. He said later, “Even in my twenties, I preferred dreaming about love and painting it in my pictures.” One can imagine this love inspired him to make Dedicated to My Fiancée, an explosive painting he completed feverishly in a single night before submitting it to a major Paris exhibition.

World War I and a Return to Russia (1914-1922)

In 1914, Chagall traveled to Berlin for a major exhibition of his work at the Sturm Gallery, where he brought 40 canvases and 160 gouaches and watercolors. After the successful exhibition, Chagall returned to Vitebsk, only planning on staying enough time to marry Bella and bring her back to France. Unfortunately, World War I broke out not long after his arrival, closing the Russian border indefinitely. This period is characterized by Chagall's musings on love and marriage, painting many scenes of the happy couple transcending borders, a real-life impossibility for them at the time. Art historian Michael J. Lewis aptly wrote of this period, “[T]he euphoric paintings of this time, which show the young couple floating balloon-like over Vitebsk- its wooden building faceted in the Delaunay manner- are the most lighthearted of his career.” This is also when, Chagall began exhibiting in Russia, first in Moscow in 1915 and then at a salon in St. Petersburg in 1916. By the October Revolution in 1917, Chagall had become a well-known artist and a member of the modernist avant-garde movement, which granted him special privileges as the ‘aesthetic arm of the revolution.’ Thus, he became a commissar of arts in Vitebsk, where he founded the Vitebsk People’s Arts School, the most distinguished school of art in the Soviet Union.

Although Chagall enjoyed success with his painting, he lived meagerly in Vitebsk and on the outskirts of Moscow with his wife and young daughter, Ida. Chagall took illustration jobs to make ends meet, where he made ink drawings for several Yiddish books. In 1921, he worked as an art teacher at a Jewish boys’ shelter for young children who lost their parents due to pogroms. Chagall designed the set for the new State Jewish Chamber Theater in Moscow in the same year. The large-scale background murals included a variety of motifs that would become staples to his oeuvre, such as fiddlers, acrobats, farm animals and dancers. The murals, which read like a dictionary of Chagall's symbols, were the forerunners of his later murals at the New York and Paris Metropolitan Operas. After tiring of the primitive living conditions and worsening famine, Chagall obtained an exit visa and moved his family back to Paris in 1923.

The Inter-War Period (1923-1941)

Before arriving in France, Chagall stopped in Berlin to try to recover the paintings he had left there before the outbreak of war, which were all lost or unrecoverable. This loss of so much of his early work pushed Chagall to reimagine his memories of Vitebsk through new works of art. Demonstrating his Belarusian Jewish origin, Chagall painted fervently, producing a massive body of work reflecting life with a childlike sensibility mixed with romantic highlights and a hint of sadness about what had been lost or left behind. The Green Violinist from 1923-24 stems from his memories of the Russian countryside in his Jewish hometown, recalling a communion of God through dancing and music. His many illustrations of fiddlers inspired the name of the 1964 musical, Fiddler on the Roof.

At this time, Chagall formed a critical business relationship with Ambroise Vollard, a well-known French art dealer. Vollard commissioned Chagall to illustrate the La Fontaine Fables (1928-31) and the Bible (1931-40). The biblical illustrations were an excuse for Chagall to travel to Mandatory Palestine, visiting Christian and Jewish religious sites, such as the Western Wall and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The trip fascinated Chagall, and he felt a kinship with the many people who spoke Yiddish and Russian, prompting him to stay for two months. Chagall reminisced on the trip that Israel gave him “the most vivid impression I have ever seen” and that “In the East I found the Bible and part of my own being.” From this point forward, the Old Testament and Bible became primary inspirations Chagall drew from, working obsessively to recreate an air of the whimsical religiosity and self-reflection he experienced in the Holy Land. These motifs inspired one of his most well-known works, the White Crucifixion.

In 1938, at the age of 51, Chagall painted a crucified Christ, covered in a white prayer shawl, as a symbol of the suffering of all Jews. In the face of Adolf Hitler and the growing Nazi movement, Chagall called out the injustices being committed to European Jewry, painting the burning synagogues and emigrants fleeing that was playing out on the other side of Europe. At this time, Chagall's paintings were facing major criticism in Nazi Germany for degeneracy, leading to more destruction of his artwork. Not long after, the Vichy puppet government began in 1940, waking Chagall up to the danger his family would face. Chagall and his family escaped to the South of France, where his inclusion on a list of prominent artists whose lives were at risk prompted the United States to extricate him. Thus, in 1941, Chagall was stripped of his French citizenship and moved to New York City.

A Brief Stint in the United States (1941-48)

At 54 years old, Chagall found himself in a new country, attempting to learn a new language and among a new artistic community with different priorities than himself. The European conflict emboldened Chagall's folklorist commitment to Russo-Jewish imagery and mysticism, reflecting on his relationship with emigration. Chagall found a sense of homeliness in the many Jewish communities in New York City, where he could read a Yiddish newspaper for news and enjoy Jewish foods. This period is marked by its darkened palette and tragic imagery, much like the 1945 painting About Her.

The news of the destruction of Vitebsk and Nazi concentration camps, coupled with the sudden death of his beloved wife Bella in 1944 to a viral infection, rocked Chagall's world, where he stated, “Everything turned black.” The months after Bella's death were the most silent in Chagall's artistic production. When he did return to painting, the practice focused on preserving Bella's memory along with the many Jewish lives lost in Europe.

As the war wound down and the Allies liberated France, Chagall longed to return to Paris. He reflected on his ambivalent time in America, “I know I must live in France, but I don't want to cut myself off from America. France is a picture already painted. America still has to be painted. Maybe that's why I feel freer there. But when I work in America, it's like shouting in a forest. There's no echo.” Thus in 1948, Chagall resettled in France, where he would stay for the rest of his life. One of his other notable works during this time was his paintings on the ceiling of the Paris Opéra House. Commissioned by Minister of Culture André Malraux in 1964, the nearly 2,600-square-foot canvas stands out for its vibrant colors paying homage to major composers and portraying notable Parisian monuments.

Legacy and Later Life:

Compared to Chagall's earlier periods, the works Chagall produced in the latter part of his career were more melancholy in both subject and color, as well as more abstract in form. Chagall returned to the same motifs of the Russo-Jewish countryside, reimagining the Europe of his youth that was now lost. He also maintained the use of vibrant color, even if paired with a darker background, such as his 1973 work Mère et enfant sur l’âne marron. This is visible in Musicians sur fond Multicolore, a masterpiece that offers a captivating glimpse into the artist's most cherished motifs.

It was in the twilight of his life that Chagall also began experimenting with other mediums. Most notably, this period is marked by the creation of stained-glass windows, starting in 1956 at age 70. These windows enhanced the effect of light on Chagall's colorful works. They decorated the walls of cathedrals and synagogues in Europe and America, including a work entitled Peace for the United Nations building.

When he passed away in 1985, at 97, Chagall was still actively painting and working in other mediums. Always the avant-garde artist who stayed true to his folk roots, Chagall pioneered modern art and was one of the greatest figurative painters of the 20th century. In the face of a life filled with discrimination against Judaism, emigration, and the loss of his great loves, Chagall made a breakthrough in self-expression through art. He distilled his identity, fondest memories and sadness into his paintings, creating an other-worldly symbolic landscape that any viewer could respond to. His tranquil figures and enigmatic colors produced a sense of monumentality, reimagining Jewish cultural motifs and values that had been long ignored in painting. French novelist and art theorist André Malraux said it best: “[Chagall] is the greatest image-maker of this century. He has looked at our world with the light of freedom and seen it with the colours of love.”

Today, Chagall’s work is highly sought after by collectors. His distinctive style and vibrant colors have made him a key figure in modern art. M.S. Rau proudly offers a curated selection of Marc Chagall original paintings for sale. For more information, please contact us today.