1. The Enchantment of the Countryside: Landscape Paintings

Natural landscapes have long inspired artists, owing to the innate splendor of the natural world— landscape oil paintings hold a significant place in the canon of art history. The Impressionists' fixation on capturing the interplay of light on ephemeral marvels continued with the Post-Impressionists. Amidst the surge of the Industrial Revolution, numerous painters embarked on journeys into the countryside, seeking inspiration and respite from the bustling urban environment.

For artists including Monet and Cézanne, the idyllic rolling hills of the French countryside became a cherished muse, while Van Gogh honed his craft amidst the rustic charm of The Hague in the Netherlands. These pastoral havens, with their isolation and scenic splendor, emerged as favorite destinations for artists, providing an uninterrupted sanctuary for their creative endeavors.

Moreover, the allure of rural life held a romantic appeal for art patrons, further enhancing the draw of these locales. Since more people had begun living in cities after the Industrial Revolution and the cost of travel was high, living in nature became highly romanticized, sometimes even seen as divine.

Soleil levant, vallée de la Dordogne by William Didier-Pouget. Circa 1915. M.S. Rau.

The splendor of the French countryside is on view in William Didier-Pouget's masterpiece, Soleil levant, vallée de la Dordogne. The artist is associated with later Impressionism, beloved in his time for landscapes and transient scenes such as sunrises. This monumental landscape oil painting expertly captures the sunrise's golden hues, transporting viewers to the picturesque Dordogne Valley in France. Didier-Pouget always painted outdoors, or en plain air, valuing the details and colors that could only be granted in person. With meticulous attention to detail, the painting exudes serenity and grandeur, enhanced by its immersive scale, spanning over 8 feet, transporting the viewer into the countryside.

2. Industry and Art Technology

The Industrial Revolution also brought about significant advantages, particularly through the invention of portable tube paints, which revolutionized artistic methods. This innovation liberated painters from studio constraints, allowing them to capture the essence of nature en plein air. Consequently, travel became desirable to the artistic journey, as exemplified by the Impressionists' pursuit of capturing fleeting moments. Much of the Impressionists' focus was on capturing what is ephemeral: sunsets, light upon water, or even a feeling at a party. To best capture these passing moments, the artists had to break free of their studios and paint moments on the road. The best place to paint a sunset was right in front of it.Monet's dedication to painting the same garden repeatedly throughout his career illustrates this shift, a project unfeasible within the confines of a studio. The artist will paint the same place over and over, in different seasons and at different times of day. Each of these new canvases holds an entirely different feeling, capturing something special. Excited by the prospect of new scenes and qualities, artists embarked on adventures armed with conveniently packaged paints, a walking stick and an umbrella.

3. Cities of Inspiration

To many artists, rural retreats offered much-needed quiet. To others, however, cities provided a vibrant well of inspiration, beautiful in its own right. With their burgeoning populations and constant influx of newcomers, cities evolved into vibrant hubs where ideas, cultures and artistic expressions intermingled. Iconic cities like Paris, Venice and Florence emerged as epicenters of the art scene, enticing creatives with their distinct blend of cultural richness, architectural marvels and thriving artistic communities.The esteemed art institutes in these cities, such as the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the Royal Academy of Arts in London, provided illustrious histories, attracting aspiring artists from around the globe. This convergence of diverse perspectives gave rise to innovative artistic movements, as creators drew inspiration from one another, fostering the development of fresh and pioneering styles. Cubism, for example, was invented in Paris between 1907 and 1914 by Pablo Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque who had come into contact with the work of visionary Paul Cézanne and African tribal art from Palais du Trocadéro, a Paris ethnographic museum.

Without these influences, this cutting-edge form of abstraction may never have been popularized throughout the creative community living in Paris at the time. Polish artist Louis Marcossis, influenced by Braque's work from 1910, refined Cubism with a lighter touch. By 1911, Spanish artist Juan Gris distinguished himself by prioritizing the essence of objects over their abstraction. Marcel Duchamp engaged with Cubism from 1910, though often diverging from it. His renowned 1912 painting, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), reflects Cubist influence with a dynamic figure, capturing multiple perspectives akin to motion. Typically, Cubist art immerses viewers in dynamic perspectives, as if the artist traversed around the subject, encapsulating all angles in one composition. These new ideas melded together at the turn of the century and have come to influence Futurism, Constructivism, Abstract Expressionism and others including modern works.

4. Foreign Vacations for Artists

Starting as early as the 15th century and reaching the height of popularity in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Grand Tour stood as a revered rite of passage for young aristocrats, who traversed iconic European cities such as Paris, Venice, Florence and Rome, culminating their classical education. Amidst this journey, they frequented museums to behold Renaissance masterpieces, long studied in literature. Michelangelo’s David (1501–1504) in Florence, Italy has served as the inspiration for countless sketches, continuing to teach young artists about perspective and form. Venus of Urbino (1534) by Titian at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy inspired Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) and Paul Gauguin’s Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892). As Pablo Picasso is widely quoted as having said, “good artists borrow, great artists steal.”

These encounters, alongside exposure to renowned architecture and vibrant cultures, profoundly influenced the future artistic and literary endeavors of travelers. Local artists also benefited from this tradition when tourists would buy cityscapes of their favorite destinations to take home as a keepsake of their adventures. Small paintings were used like modern-day postcards, along with other options such as etchings, micromosaics and pietre dure. Micromosiaics and pietre dure were particularly sought after as they could include stones sourced from local areas, tangible evidence of these adventures.

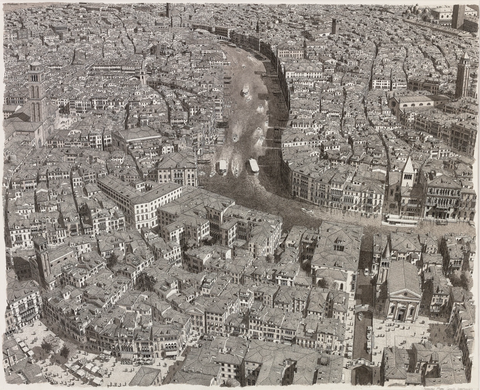

View of San Giorgio Maggiore by Giacomo Guardi. Circa 1804-1828. M.S. Rau.

5. Coastal Escapes

The seaside has universal appeal, even for artists whom you might expect to find only holed up in their studios. Brittany, situated in France's northwestern region, proved to be a wellspring of inspiration for numerous post-impressionist painters.

They were drawn to its rugged, dramatic coastline and lush forests which became an arts center. Renowned figures in the art world, including Pablo Picasso, Claude Monet and Henri Matisse, found themselves captivated by Brittany's varied coastline and untamed scenery, making it a favored destination for those seeking artistic stimulation amidst nature's wild beauty.

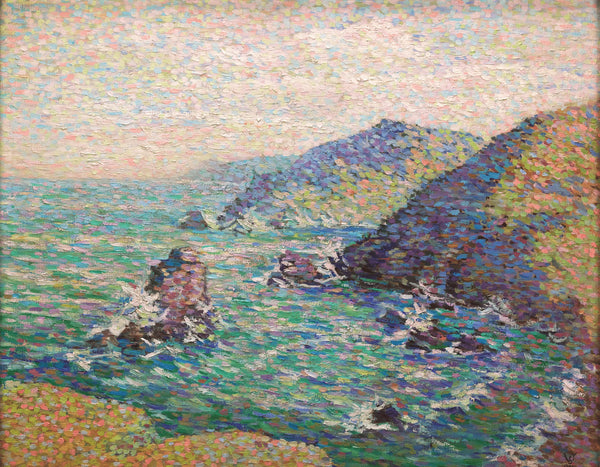

Les falaises by Willy Schlobach. Circa 1907. M.S. Rau.

Prior to the 18th century, indulging in a day of repose and leisure by the seaside was not the cultural norm. The coastal environment bore connotations of peril and untamed wilderness, intertwined with narratives of shipwrecks and pneumonia. The sea commanded reverence, perceived through a lens of divinity.

Consequently, early depictions of seaside landscapes garnered heightened intrigue, representing a curiosity seldom witnessed firsthand. Rendering the ocean on canvas was tantamount to encapsulating the divine essence. By the 17th century, Dutch maritime artistry not only evoked fascination but also stimulated tourism to coastal locales, enticing visitors to behold the very panoramas immortalized by the artist's gaze.

6. The Exotic and the Unknown

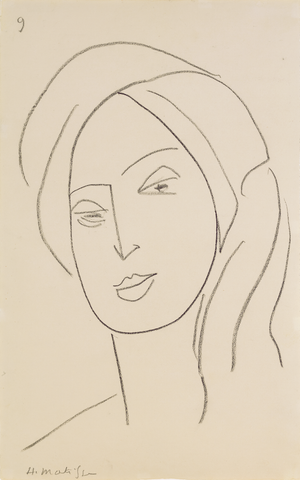

Other artists chose to travel farther in their quest for inspiration and explored diverse landscapes to fuel their creativity. Henri Matisse, for instance, found Morocco to be a profoundly different and exotic setting, leading him to produce numerous sketches, drawings and paintings inspired by his experiences there. Entranced by the region's warm Mediterranean light, Matisse infused his artworks with a luminous quality reflective of his impressions.Matisse was deeply struck by Moroccan culture; the vibrant attire, architectural splendor and everyday customs. This fascination is evident in his works from the period spanning 1912 to 1913, where he depicted men and women adorned in traditional colorful garments such as jellabahs and gandouras, as well as scenes of daily life. It seemed as though the vibrant and flamboyant use of color across all aspects of life in Morocco effortlessly aligned with the bold stylistic preferences of Matisse's Fauvist approach.

French Orientalist painter Raphaël Pinatel extensively traveled to Northern Africa, aiming to portray the allure of the East for Western audiences. His experiences in Morocco profoundly influenced his artistic output.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was significant European demand for Orientalist artworks. In response to this trend, Pinatel co-founded the Association of French Painters and Sculptors of Morocco in 1922, along with eleven other artists. The group frequently exhibited together, garnering both popular and critical acclaim and satisfying the contemporary fascination with exoticism. This oil painting by Pinatel depicts a market scene in Taroudant, a city in southeastern Morocco, serving as a captivating tribute to the Moroccan landscape.

Taroudant by Raphaël Pinatel. Circa 1926. M.S. Rau.

7. Island Living

Paul Gauguin, the famed Post-Impressionist, is perhaps best known for his well-documented journey to Tahiti— a pivotal shift in both his personal life and artistic career. As he immersed himself in the island's vibrant culture, his creative output flourished, accompanied by a notable evolution in his painterly style. Tahitian life gradually alienated him from his European roots, drawing him deeper into the mesmerizing realm of his sunny paintings.Gauguin's works from this period diverged from his earlier impressionist style influenced by Pissarro, evolving towards a more abstract aesthetic. Colors became more vibrant, shapes bolder and more stylized, while his subject matter increasingly centered around the Tahitian women engaged in their daily activities.

Deeply enamored with Tahitian life, Gauguin found himself captivated by the island's natural beauty, igniting within him a newfound zest for existence. In his journal, he vividly recounts his experiences in Tahiti, painting fantastical images with rich descriptive prose that captures the essence of his profound connection to the island and its people.

This firsthand familiarity with his surroundings is evident in his artwork, where his visual narratives stand apart. Combining the rationalist style of historical paintings with a theatrical Romantic aesthetic, Gérôme's works exhibit a unique blend of artistic license and authentic experience gleaned from his travels.

8. Japonisme

Farther east, Japanese art had a profound impact on Western artists during the late 19th century, particularly during the Impressionist movement, known as Japonisme. This trend surged after Japan reintroduced itself to the West in 1853, introducing its culture and goods to Europe. Coined by French collector Philippe Burty in 1872, Japonisme gained traction as Western artists were captivated by Japanese art.Impressionists like Edgar Degas, Claude Monet and James Tissot amassed vast collections of Japanese art. Monet's Japanese Bridge paintings were directly influenced by ukiyo-e prints, infusing Impressionism with a Japanese aesthetic.

Vincent Van Gogh, initially slower to adopt Japanese art, was deeply influenced by it. His love for nature, reflected in ukiyo-e landscapes, inspired his move to Arles in southern France to authentically recreate the Japanese style he admired.

New Landscapes

Numerous modern and contemporary artists, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, have embarked on journeys in pursuit of their art, finding inspiration in new landscapes. Today, with air travel more accessible than ever, artists can more easily traverse the globe or even explore virtually from their computers.21st-century initiatives such as Virtual Paintout utilize tools like Google Street View to provide artists with distant references, enabling them to capture the essence of far-off destinations with a simple click. So, with a vast history of artistic travel and the world at your fingertips, where will your artistic journey take you next?

For further reading, here are some artists who were inspired by their travels.

Wassily Kandinsky: Visited Tunisia and other North African countries.

Gustav Klimt: Influenced by trips to Italy and Egypt.

Mark Rothko: Traveled to Greece and Italy for inspiration.

Ansel Adams: Captured the spiritual essence of West in American art.

Piet Mondrian: Inspired by his travels to Paris and later New York City.

Beeny, Emily. 2010. Blood Spectacle: Gérôme in the Arena. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. 42.