The following is a transcript from Bill Rau's Keynote Speech from the American Cut Glass Association Convention:

INTRODUCTION

Many years ago, there was a brilliant Wedgwood dealer in Philadelphia by the name of Seal Simons. In the early 1980s, when I was still cutting my teeth in the business and I would get a unique piece of Wedgwood, I would often call Seal to ask her for advice because I felt she knew everything.

Many years ago, there was a brilliant Wedgwood dealer in Philadelphia by the name of Seal Simons. In the early 1980s, when I was still cutting my teeth in the business and I would get a unique piece of Wedgwood, I would often call Seal to ask her for advice because I felt she knew everything.

I remember being very aghast one time when I called her up and asked her something about an 18th century black basalt Wedgwood vase, and she said, “I don’t know.” I was shocked because here I was, thinking she knew everything.

I remember asking her, “How do you not know the answer?” Her reply was, “Well, I need to ask people who know more than I do.” I remember stating, “Seal, all you deal with is Wedgwood- nothing else! And you have been doing it now for 50 years. How can other people know more than you do?”

She said, “Sure, all I deal in is Wedgwood. But there are people who only collect black basalt Wedgwood, and then there are people who only collect black basalt of the 18th century, and there are people who only collect black basalt from the period of the 1770’s to 1785. And many of these people have read every single book and article that’s ever been written about this period. These are the people I go to when I need information: the true, true experts."

I share this story with you today because I feel like when I speak to you I am speaking to many true, true experts on cut glass. So instead of talking about why this pattern is wonderful, or what makes this shape so special, or some very interesting fact about Thomas Hawkes, I want to take you on a historical journey on why cut glass came to succeed in the United States of America. To understand that, we’re going to start a long, long time ago.

Let us start with arguably the most important piece of glass in the entire world. Surprisingly for many of us, it is not a piece of American Brilliant period cut glass. It is the Portland vase.

Made roughly two thousand years ago by Greek artisans, and presently housed in the British Museum, this vase – I believe most experts would agree - is the most famous piece of glass ever made. It is famous for a variety of reasons. It tells a story, although, ironically, all experts do not agree on what the story actually is.

It is cameo glass, and it is also the finest example of ancient cameo glass known. If you think of how American Brilliant period color cut to clear glass is made, this vase was created in a very similar fashion. It started with a base of blue glass and then they would blow a layer of white glass put on top of it. The artisan would then cut through the white to get to the blue, and what was left made the design.

We start with this treasure because it comes from the very first period of blown glass. Even though glass had been made for thousands of years before this, blown glass was not invented until roughly 20 B.C. However, before there was blown glass, there was still decorative glass which was mostly made in Egypt.

Here is a picture of an Egyptian glass alabastron, made roughly 250 years before the Portland vase.

Since they did not know how to blow glass, how did they actually make it?

First, they would get wet cow dung and make a reverse mold, then take a string of glass and wrap it around the base. They would let that string dry and then put a different color string of glass on top of it. They would continue doing this and eventually make lovely patterns like this one. Then they would rinse the dung out of the completed vessel and use it for perfume. (I am quite sure many of us in this room could concoct some good humor about the perfume and dung combination, but fortunately that is not part of this speech.)

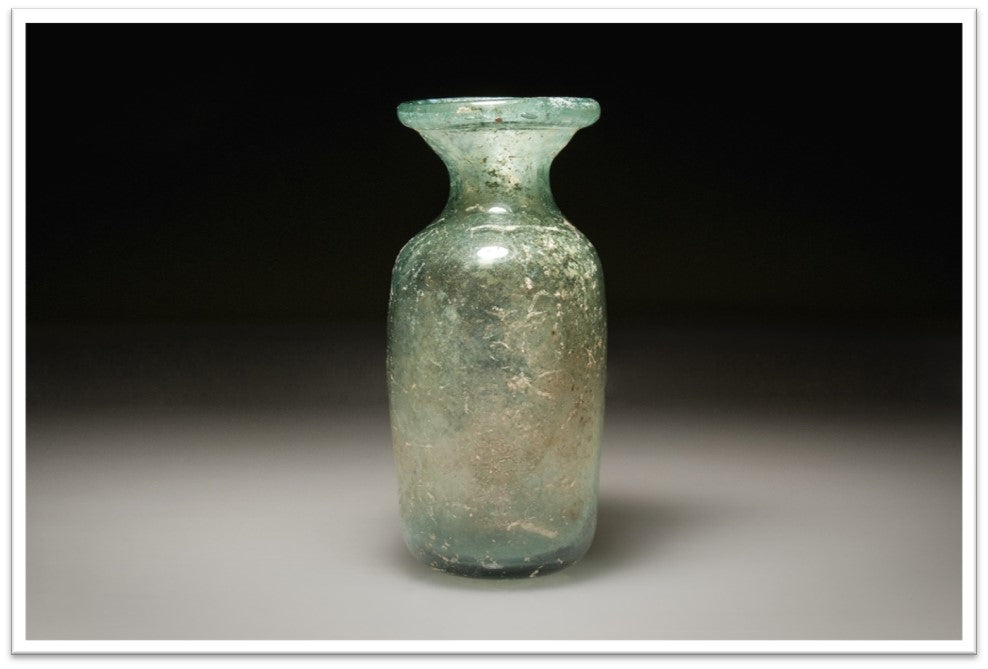

Here is a picture of a typical piece of Roman glass that was blown circa 300 A.D., about 500 years later than the the Egyptian Glass Alabastron.

Certainly not as exciting as the Portland Vase, but much, much more common. Ironically, ancient Roman glass is almost never found in Italy or anywhere in Europe. The only Roman glass that was found in quantity on the continent was unearthed at Pompeii, and that was of course due to the entire city being instantly entombed by volcanic ash in 79 A.D. The reason for this lack of Roman glass being unearthed elsewhere in Europe is that the moist and fertile soil on the continent would decay the glass too quickly, and thus it did not survive. The great, great majority of Roman glass that has been found was unearthed in the Middle East because when the glass was buried in sand it decayed much more slowly.

As you hopefully can see, Roman glass typically has these wonderful iridescent colors. When the Romans originally made it, it did not have this iridescence. This is the direct result of the glass decaying. Once it was buried for a thousand or fifteen hundred or even two thousand years, it would acquire this beautiful iridescent glow.

Here is a piece of Louis Comfort Tiffany glass made about 1910, roughly 16 centuries later than our Roman glass example.

Louis Comfort Tiffany admired Roman Glass so much he modeled his famous Favrile glass, with its intentional iridescence, after it.

Rome falls, and for roughly 600 years glass goes into a virtual hibernation. It is still made in a handful of places in the Middle East but only in very small quantities, and how to make it is essentially forgotten on the continent of Europe.

A highly important sociological theory that pertains to why glass ended up succeeding in America is known as trans-cultural diffusion. Its definition is: “The spread of cultural items such as ideas, styles, technologies, and languages between individuals, from one culture to another.” This is really, really important, and I’ll explain why.

For roughly 600 years after the fall of Rome, not much happened in Europe. That is obviously why it was called the Dark Ages. Then a number of huge events happened, one after another, with the first major one starting in 1095. That, of course, was the very first Crusade. Basically, someone from England went to France and said, "We need to rescue Jerusalem from the Muslims," and they both went to Germanic States. Eventually, they got noblemen from all over Europe who had never physically met before, and they all traveled together.

They went to the Middle East (then known as the Near East) and met thousands of different types of people with different ideas, different technologies, and different philosophies along the way. When the Crusaders returned to their homes in Europe, they brought many of these “foreign” ideas back with them. That was the beginning of the end of the Dark Ages.

Right around that time, not coincidentally, is when glass came back to Europe. How did it come back? First it came back as stained glass in churches.

Stained Glass, Chatres Cathedral, France

The artisans, many that had been glass-makers in the Near East, figured out how to put color into glass. Architects then put these beautiful windows in a handful of the most important churches they built. Why church windows? Because what was the most important building of any European city? The central church. Stained glass was exceptionally expensive, and who else could afford this luxury besides the Church? Also, from a practical standpoint the stained glass let light in without allowing those within the building to see out, thus kept the parishioners’ minds on the church services.

Despite the glorification of the Crusaders by many today, the Crusaders themselves weren’t necessarily the nicest people. In 1204, the 4th Crusades began, mostly led by the Venetians this time. This is because some European noblemen decided that instead of taking the time to march all across the southeast corner of Europe they would use ships to bring them over. And since the Venetians had Europe’s largest navy at the time, they were chosen to lead. They went on this Crusade and sacked Constantinople. Now, at that time, Constantinople was not ruled by Muslims. It was ruled by the Eastern Christian church, and when the Europeans sacked it, they sacked it in style.

Sacking of Constantinople, 1204

At that time, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city in both Europe and the Near East, far bigger than London, Paris, Rome, or Venice. Constantinople was a unique place; different from the rest of Christendom. The merchants in Constantinople traded with the Muslims, as well as with the Indians and the Persians. They even traded with the Chinese. They also knew how to make glass.

When the Venetians sacked Constantinople it was quite gory. They sacked it, they pillaged, and they raped. They did everything that you would hope Crusaders would not do, especially to a fellow Christian. However, pertaining to glass, one of the most important things is that, after the sacking, they brought many of the “Eastern” glass artisans back to Venice with them. That is when the Venetians started making glass.

The Venetians quickly realized that this glass trade could be very profitable because many other Europeans desired glass. Eventually, glass became such a large business that the glass-makers themselves were forced to take over an entire Venetian island, known as the Isle of Murano. This was done for two reasons: the first reason was to keep the glass-making process secret so no one could just go by and steal the craft. The second reason was much more practical. It was because of fire. Melting glass often created fire, and in places with wooden homes, as you can imagine, fire was always a serious concern.

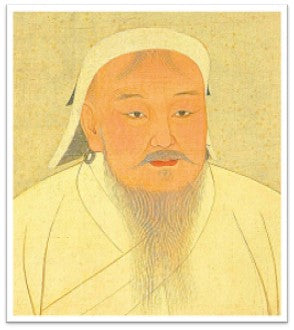

The next great event to happen in the world involved someone who has really gotten a bad rap over time, but I believe most historians today would agree that this person would make the list of top ten most important people in world history. That person was Genghis Khan.

Genghis Khan, 1152-1227

People talk about the size of the Greek Empire and how large the Roman Empire was, but nothing compares in size to the Mongol Empire, and it was at its peak around 1227 A.D. The Mongol Empire was roughly six times larger than the Greek Empire and five times larger than the Roman Empire at their heights. Why was this important? Go back to the all-important theory of trans-cultural diffusion.

In this giant Empire, you had the Mongols. You had the Tartars. You had the Chinese. You had the Koreans. You had the Persians. You had some Indians. The Afghanis, the Russians, the Ukrainians. You had the Bulgarians and the Hungarians, all under the rule of the Mongols. All of this, every land from here to there had its own ideas on how to make beautiful objects. When the Mongols captured places, they typically didn’t destroy them like many people today would think. They certainly killed some of the nobles, as they knew these noblemen could possibly create future dissent, but what they wanted to do more than anything else was to create trade.

Now, Genghis Khan was extraordinarily advanced for his time. He allowed his subjects religious freedom, he instituted the idea of diplomatic immunity, he came up with the remarkably novel idea of paper money, and he brought artisans and scholars from all over the world to the East to teach them their crafts. All he asked of his subjects was that they would pay a tax to him. This part was really no different from any other ruler. Every leader wanted taxes. They still do! Genghis Kahn stated that as long as people paid their taxes, he would protect them.

Because what Genghis Kahn really desired was trade.

This is when the Silk Road was originally opened. He wanted this trade route established so that his people, the Mongols, which were a nomadic tribal people, could get the goods that came not only from Europe, but from all over, and the Europeans and central Asians could get goods from the East that they had never had before.

Don't think for a second that the genius of the Renaissance, and the many brilliant inventions that came shortly after, did not have its seed in the Mongol invasion. One of the world’s most important Renaissance inventions that originated from the Mongols was Gutenburg’s printing press.

Gutenberg's Printing Press, Circa 1450

Gutenburg got his idea directly from China, as there were numerous printing presses being used there for over 300 years before Gutenburg invented his. Here is a picture of an early example from China:

12th Century Chinese Printing

Their models were not as efficient as his famed invention, but they were also able to print on paper. These presses were the genesis of Gutenburg’s press, which undoubtedly changed the world, but we’ll get back to this later.

Let’s fast forward a couple hundred years. The greatest power in the world at that time was Spain. The pinnacle of Spanish power was 1588, when the great Spanish Armada attempted to invade England.

Spanish Armada, 1588

With the help of Mother Nature, the huge fleet was defeated by the small island nation. This is when the British woke up and realized that naval power was all-important.

Versailles and The Hall of Mirrors

By far the largest figure in Europe the 17th century was Louis XIV. He would have undoubtedly agreed with that statement. He thought so much of himself that he wanted to construct, in his opinion, the grandest palace ever conceived. He succeeded when he built the Palace of Versailles.

For Versailles, he had a vision that he wanted to do something that nobody had ever done before, thus, he wanted to make a room with glass - specifically, a Hall of Mirrors.

Hall of Mirrors, Versailles

Now, if you and I were to walk through the Hall of Mirrors today, we’d say, “Oh, this is very nice,” but it likely would not blow us away. In the 17th century and even the 18th century though, people were in awe of this magnificent creation he built. Let me explain why.

Mirrors and glass were exceptionally expensive in the 17th century. The reason we have such decorative frames around mirrors today – here is a 19th century mirror with its decorative frame -

Baroque Mirror, Late 17th Century

glass and mirrors were so expensive that to build a decorative frame around a mirror was only a few pennies more. In other words, this mirror itself probably cost 98% of the entire package and the frame only cost about 2%. Why not make it decorative if it only added 2% more to the cost? Two hundred years later, in the 19th century, the above decorative frame probably cost 98% and the glass mirror itself only cost 2% of the total, but the ornate style of decorative frame that had begun with Louis XIV remained.

So because mirrors were so expensive, and because nobody had ever built a room of mirrors before, when the Sun King built his, it became the most famous room in the most famous building in the entire world.

The head of construction for Versailles was Jean-Battiste Colbert, the Minister of Finance under The Sun King. He decreed that every single part of the palace must be manufactured in France. The big problem was that no one in France knew how to make mirrors. The only people that the French knew who could make mirrors were the Venetians. So the Minister of Finance did the only thing he knew how to do and commenced to smuggle many of the glass artisans off the Venetian Isle of Murano. He ferreted them to France so they could make the mirrors for Versailles. The Venetians themselves were so distraught about this defection of their craftsmen that, according to legend, they actually dispatched assassins to poison these artisans so they would not be able to disclose the state’s trade secrets.

This is how valuable glass was in the 17th century. It is also how the cat was let out of the bag, and the technology that the Venetians had perfected and tried so hard to protect spread throughout Europe.

How does all this pertain to glass? It is because before this, England was basically a wood-burning nation. For their heat, and most importantly, for their industry they typically used wood. The English crown realized that they needed a large navy, and thus needed to make ships. The construction of ships took an incredible amount of wood. Somewhere around 800 fully grown, giant oak trees were needed to make just one mid-sized battle ship.

For England, which was a relatively well populated small country without a lot of forests, this was an incredible amount of wood. So the crown insisted that industry turn to coal for manufacturing. One of the by-products of burning coal was that coal would create a much higher and more consistent temperature than wood when put in an oven. This higher and more consistent heat allowed glass to be made much more efficiently. Thus, in England, the glass industry was born.

One of the reasons that Spain wanted to invade England was that they had different ideas of what proper religion was. The Spanish were obviously Catholic, and the English, post-Henry the Eighth, were mostly Protestant. If you could be transported back to the 1680’s and take a poll and ask what the most important public issue of the day was, the great majority of the people throughout Western Europe would have undoubtedly said the Protestant Reformation.

Now, I would like to believe that the people in this room could care less about the religion of the person sitting next to them. But in the 1680s throughout most of Europe a person’s religion was of vital importance. It affected every aspect of one’s social standing and ability to earn a livelihood. Guilds and fiefdoms, and lords and lordships, were gifted and influenced by what religion one practiced. To give you an example, the silver guild in France was a completely Protestant guild. Thus, if you were a Catholic and desired to work in silver, you could not get in that guild and thus could never work in silver.

The furniture-making guild in France was mostly a Protestant guild. The watch-making guild was mostly a Protestant guild. So if you loved watches or clocks and wanted to work in that field you almost certainly could not get a job, but it was even more than that. Say you were a business person, and a very successful one, but your liege-lord was Catholic and you were Protestant. You would be reluctant to take financial risk because you knew he could potentially come by and take both your business and land away.

Even if you were a Catholic and your liege-lord was a fellow Catholic this was still a problem. Maybe the regional governor above him was Protestant, and maybe they would convince your liege-lord to change religions - because people did change religions if someone offered them an incentive to do so. If he did change and all of the sudden he was not of your religion anymore, he could possibly come by and very much harm your finances.

Protestant Reformation

Towards the end of the 17th century two highly important events happened. In 1685, the French King, Louis XIV, revoked the Edict of Nantes. This was the edict which had allowed Protestants to worship in France, and most of the French Protestants fled their homeland.

Revocation of Edict of Nantes, 1685

The reason that many of you may have a Swiss watch on, whether it be a Rolex or Audemars or Patek Phillipe or even a Swatch, is that the French watchmaking guild was all Calvinist, and they emigrated en masse to Geneva. They went to Geneva because it was then the center for Calvinism. Thus the Swiss watch-making industry was born.

The furniture-makers and the silver-makers mostly went to the northern countries with a large Protestant population: England and Holland. What resulted was a classic trans-cultural diffusion. You had people who had studied and learned all these wonderful French ways of designing objects, and all of the sudden these immensely talented craftsmen were expelled from the country. When they left, they, of course, brought their knowledge with them. When they went to their new country, they typically continued in their line of work, whatever it be, making watches or furniture or crafting silver. However, now they made their goods in Switzerland, Holland or England, and they starting mixing their own particular techniques and talents with the local craftsman.

The second important event happened just three years later in 1688. That is when England’s last Catholic king, James II, was overthrown by his son-in-law and daughter, William and Mary.

William and Mary of Orange

James was actually a pretty good king, but the English didn’t like him for the simple reason that he was Catholic. So the English Protestant elite hired a bunch of mercenaries and then convinced his son-in-law, the Dutch ruler, William of Orange, to invade. James II didn’t even put up a fight; he just fled to Ireland. And William became king.

Until that time, there was no law stating that the English king had to be a certain religion, but then the English did something very clever. They changed the law to state that from that moment on, the king had to be the head of the Church of England and thus, de facto, a Protestant.

With that event, a giant sigh of relief emerged all over western Europe. The sigh of relief was because for the very first time, people felt comfortable that there were not going to be any more giant religious upheavals. If you were a Protestant in England - or even if you were a Catholic - you would know where you stood. The Protestants no longer had to worry about the Catholics taking over, so, ironically, there became less prejudice against the English Catholics.

In France, there were very few Protestants left at this time, but even the Catholics in France now knew that their land would not be taken over for religious reasons. So the first by-product of these two important events was that, for the very first time in history, people felt secure enough to build large homes.

And the second by-product of what happens when you have a big home? You need decorative arts to fill them.

Another important consequence of these major events, not unlike the Fourth Crusade or the Mongol invasion, was that movement of craftsmen, with one culture bringing its traditions and techniques and combining it with another, created far better objects. It was these two events that directly led to the growth of the decorative arts business.

The 19th Century

And now we move on to the 19th century. One of the most important events that happened in the first quarter of the century, happened in the United States - and this is the first time we have really spoken about America. It occurred in 1825. This was the opening of the Erie Canal.

Erie Canal Opens in 1825

The Erie Canal is only roughly 40 miles from Corning. This one giant canal opened up hundreds of other trade routes.

Twelve years later, in 1837, the telegraph was invented by an American, Samuel Morse.

Samuel Morse and the Telegraph

This is also very important. We’ll get back to this in a little bit.

One of the most monumental events of the 19th century - and this happened in many places in the western world - was the rise of the Middle Class.

Before the Industrial Revolution, there were really only two classes. There was the upper class and there was everybody else. Beginning in the 18th century, and coming to fruition by the mid-19th century, there was a prominent middle class. One of the things that middle class people always wanted to do was emulate the upper class.

Let’s move back to Paris for one second. Here is the wonderful Passage des Princes in the Rue Richelieu.

Passage des Princes, Circa 1860

This is one of the very first places that the middle classes could go shop for decorative wares after dark. Why is that important? If you think about the 19th century, first of all, middle class men typically worked and thus they could not go shopping with their wives during the day. Also, in the 19th century and through the early 20th century, it was often unfashionable for females to go shopping for decorative wares alone as they could be deemed risqué.

But what really made this passage successful was another invention - gas lighting. Now, with gas lighting as well as a glass ceiling, one could shop in these venues during the day and at night, no matter what the weather.

And with stone and tile floors, the women could wear their fashionable shoes and “Sunday” clothes because they didn’t have to worry about stepping in mud (or something worse) while they shopped. Thus, they could look their best. And what did these middle class people shop for? They shopped for decorative wares.

These 19th century malls revolutionized the experience of shopping and also how goods were merchandised. It was here that the concept of a “boutique” which sold decorative wares was born versus a regular old “shop” which sold only necessary goods.

The merchants of these boutiques typically lived upstairs above their stores and would display their wares beautifully in their shop windows. The merchants themselves, in order to make a living, desperately needed to differentiate themselves from each other. How did they do that? They would ask their artisans, "Can you make something different? Can you make something better? Something prettier? Can you make something that no one else has?" Thus, market conditions caused increasingly superior decorative goods to emerge.

One of the plethora of events that helped cut glass succeed in America happened in 1868, when great amounts of silica were discovered in the western states, first in Nevada, but soon after in other places. Silica is the main ingredient in glass. Sand is also silica, but beach sand is never good for glass because it bears too many impurities. Silica, or Quartz sand, is far purer. The purer the silica, the clearer the glass, and the silica that was discovered in the American west was remarkably pure. This great find allowed American glass to be made much finer than it had been made before, and it could also be made cheaper and in greater quantities.

The very next year, in 1869, the Transcontinental Railroad opened.

Transcontinental Railway, Completed 1869

This was important for numerous reasons. It created enormous wealth, as the great, great majority of affluent Americans either made their fortune from transportation or financially benefited when transportation became more efficient. It created thousands more shipping routes. It allowed the silica to get back from Nevada to Toledo and Corning, as well as other places that glass was being made. It also facilitated transcontinental diffusion of ideas, tastes, wishes and wants. An ironic reason that cut glass did not truly succeed in Europe where it had such a head start and yet did succeed in America is because in Europe they had been manufacturing it for too long. What I mean by this is, when somebody has been doing something successfully the same way for a long time, they are often quite reluctant to change the ways they need to do things to survive.

A business professor of mine once commented that some businesses that have been around for half a century may think they have fifty years’ experience, but what they really have is one year of experience, fifty times. When a company is psychologically incapable of making technological changes to improve, ironically, often because they have been successful in the past, they are almost always doomed to failure. Also, when somebody starts afresh they typically start with brand new technology. Don’t think for a second that Japan's rise in the 1980s, when they made cars that were better and cheaper than the Americans, was not due in part to their starting with fresh technology and not being burdened by doing things the old way. A comparison can also be made to China today. Some things they make far more efficiently than we do for the simple reason that they’re not sitting there with old factories and old methods. They are much more capable of being efficient.

Josiah Wedgwood may have been among the first to advertise his decorative wares, but the American cut glass manufacturers perfected it. They perfected it because they were fortunate enough to manufacture something that could be drawn by hand and still look good in black and white print.

Hawkes Advertisement

Please keep in mind that in the 19th century, the technology did not yet exist to reproduce photographs in magazines and newspapers. Thus, cut glass, because it could be drawn well in black and white, could be advertised all over. Whereas furniture makers and rug manufacturers and curtain designers often could not show how wonderful their products actually looked, cut glass makers could get their point across.

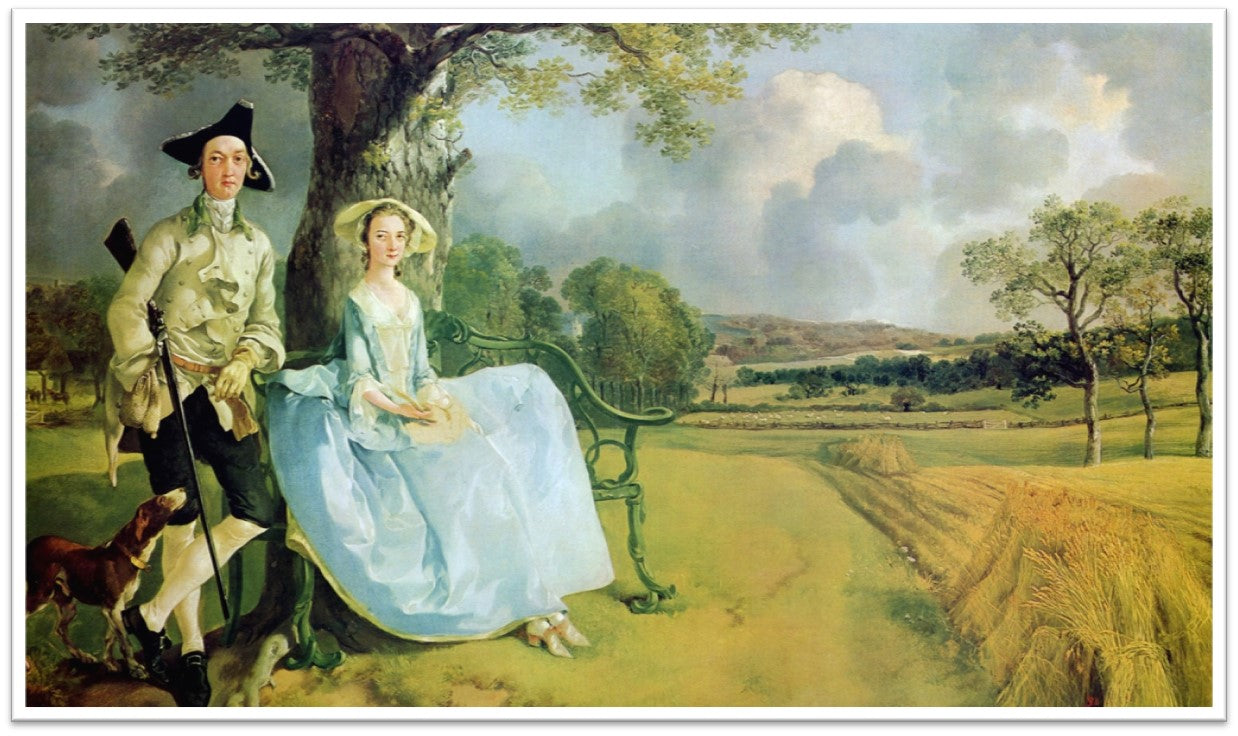

We are all familiar with the law of Unintended Consequences. We also know that when a government institutes a tax, it rarely goes away and it typically goes up. One of the reasons that America is the land of antiques and we have more fine antiques here than anywhere else in the world, ironically lies in the English tax system. Well over 100 years ago, some clever English politician had the grand idea of putting an estate tax on all the great English landowners of the time.

Mr. & Mrs. Andrews by Thomas Gainsborough

This tax started out at only three percent of one’s estate. That does not sound like a lot. If your estate was worth a hundred thousand pounds and you died, your family would have to pay three thousand pounds in tax, but they forgot to put a marital exclusion in there. So, if Mr. Andrews died one year and Mrs. Andrews died the next year, not only did their heirs have to pay the tax once, they had to pay it twice. Ordinarily, even under most circumstances, this would not be that onerous of a tax.

One of the important things that most people do not remember about the English upper classes is that they did not typically work. If you were a gentleman of high social status in England in the late 19th century there were only three noble professions available to you. If you worked in any profession besides these three you would be considered unfit for society. These professions were the church, politics, and the military. Thus, the great majority of the English upper classes didn’t work in any of these professions. They just lived off the wealth from their lands, however, they did not work the land themselves. As a general rule, they rented the land to farmers who were the equivalent of share-croppers, who would then pay them rent with a percent of the crops grown.

A moment ago we talked about the railroads crisscrossing America, and how transportation had become very efficient. This new technology had an interesting side effect: America was now able to produce food that was less expensive than the rest of the globe. This is when we became known as the bread-basket of the world. We could produce food less expensively because not only did we have the fertile lands, we also had the network of railways to transport the food, as well as faster ships. Thus, we could deliver food from the United States to Europe which was thirty to fifty percent less expensive than the food they were growing over there, and for the first time in history, food prices around the world fell dramatically.

So the English landed gentry with their giant homes were now being taxed and were not taking in enough money from their tenants to keep up their homes and their lifestyles. Often, the very first thing they sold were their valuable antiques and decorative arts, and they typically sold these treasures to the Americans.

The world had changed, and the people with the real money in those days were the Americans.

Needless to say, as money was leaving Europe, because there was more money to be made in America, immigration to America picked up. When immigration picked up, trans-cultural diffusion helped bring even better ideas to our factories. Very few of the workers of the American Brilliant period were actually born in America. They came from the British Isles, England, Scotland and Ireland. They came from Russia (which then included Poland), from Sweden, and from Germany. They came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including Bohemia, and from Switzerland, Belgium and France.

Please do not think for a second that each one of these people, most of whom were trained in factories in Europe, did not bring their knowledge with them and say, “We have done it this way!” And the people working in America said, “We do it this way!” Then they would use their combined knowledge to make something even better than what had been made in their old country.

A superb example illustrating this transfer of wealth pertains to the 1889 Paris Exhibition. This was, of course, the Exhibition where the Eiffel Tower was unveiled.

Eiffel Tower, Built 1889

It was also the Exhibition where American cut glass strode to the front of the world for the first time when Thomas Hawkes won the gold medal for the glass he displayed there.

Winning for the Americans was a major event, because keep in mind that in those days the fairs did not have international judges. For an American company to go to Paris and win, with French judges against Baccarat and St. Louis and even Val St. Lambert, was quite the statement.

But here’s the really amazing fact: the largest structure in the world, the famous Eiffel Tower, was built by the entire French nation for this fair. The construction used more iron than any building that had ever been built. It was not only the largest monument ever made in square footage; it was also the tallest structure in the entire world. However, the giant Eiffel Tower was not the most expensive project being constructed in the world that year. A vacation home, intended to be used only three months a year, was being built that same year — a home by the name of Biltmore.

Biltmore House, Built 1889

It was being built in Asheville, North Carolina by the Vanderbilt family, and that single vacation home cost more than the entire Eiffel tower.

There can be perhaps no clearer indication of the transfer of wealth to America than this one little example, and Americans that were wealthy wanted to show their wealth.

In 1890, if you were lucky enough to be invited to Buckingham Palace to dine with the queen, you would have likely been seated at this exact table here and possibly have had this exact silver put in front of you.

If you notice, there are only seven pieces of silver at the place setting: three forks, three knives, and one spoon.

Say right after that you took the boat back to America, and three weeks later you were invited to dine at J.P. Morgan’s mansion in New York City.

Here’s a Tiffany set that we've owned from this period that has 639 pieces of silverware in it. Each person at that dinner would have potentially had 29 different pieces of silver put in front of them.

This was the Americans’ way of showing their wealth.

And, of course, if you had all these pieces of silver they all had to have a specific use. You had to have a pickle fork, and a strawberry fork, and an ice cream spoon, and an oyster fork, and a cheese scoop, and a mustard spoon. And, of course, these silver pieces needed to have specific dishes to go with. If you had a pickle fork, you needed a pickle dish. If you had a strawberry fork, you needed a strawberry bowl. If you had an ice cream fork, you needed an ice cream dish. If you had a cheese scoop, you needed a cheese dish and dome. The silver that was created for the wealthy needed their cut glass counter parts.

But it was not only the super-wealthy that helped American cut glass succeed. The middle class was also getting wealthier. Henry Ford started paying his workers five dollars a day which was then unheard of. It was double the wage paid by other employers. He did this because he said he wanted his employees to be able to buy Ford cars.

The Roman writer Terrence, writing in the second century BC, stated, “Nothing is said that has not been said before." He said that 22 hundred years ago. Many of us believe that most of the American Brilliant period cut glass designs were unique patterns. But these patterns were almost always based upon designs that the Europeans brought with them - often patterns found in old world architecture or art.

Here you can see how the American Brilliant Strawberry Diamond and Fan pattern reflects the elegant woodwork designed by an Italian craftsman in the Renaissance.

Strawberry, Diamond and Fan Pattern

St. Zaccharia Church, Venice

Here’s this Pairpoint Bowl and an exterior detail from the Bahai Palace in Marrakesh, Morocco.

Pairpoint Catalpa Bowl

Bahia Palace, Marrakesh

Here, the Hawkes Panel pattern recreates the movement and symmetry of this beautiful 13th century window from Chartres in France.

Hawkes Panel

Stained Glass at Chartres Cathedral, France

Here’s the cane pattern, perhaps in part inspired by this mosaic pattern in the floor of Saint Mark’s Church in Venice built in the 9th century.

Cane Pattern

Floor of Saint Marks, Venice

And this Hawkes Iris, an homage to the artistry both of Mother Nature and the French Impressionists who were painting at the same time of the American Brilliant glass movement.

Hawkes Iris, 1903

Van Gogh's Irises, 1889

The Americans designers did not invent these patterns. They just perfected them in cut glass.

America had the wealth. We had the silica. We had the ability to efficiently transport breakable goods.

Here’s a map of the railroads in 1890.

Railroads of America, 1890

This is a map of only some of the great American canals – this map is actually only through 1860. I could not find a presentable one from 1890.

Canals of America, 1860

We had the workers who had brought their skills and crafts from all over the world. We had trans-cultural diffusion. The melting pot that was America perfected the glass.

Many years ago, my then-young daughter looked at me and said, “Dad, your head has a lot of useless information in it.” So how does all this useless information we’ve been speaking about add up?

Here’s a picture of the portrait of Madame X, painted by the famed American artist John Singer Sargent. Madame X’s real name was Virginie Amélie Gautreau. Even though she lived most of her adult life in Paris, her true home was just a few blocks away from where you sit now, in New Orleans. While she was living in Paris, on a specific Saturday night, she was entertaining some friends at a party. At that party, she was using her Thomas Hawkes punch bowl. A Parisian society writer who loved to write about the wealthy penned a article about the party and the punch bowl. Then, her newspaper telegraphed this story to New York using Samuel Morse’s invention of the telegraph, not to mention the American ingenuity that ran the transatlantic cables under the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. On Sunday, the day after Madame X’s party, the story was printed by the New York Herald.

The very next day, in Peoria, Illinois, the local paper, using a more advanced version of Gutenburg’s printing press, runs this story. In Peoria, a middle class woman reads the newspaper and sees this story. She’s made her living by selling her farm goods to the Europeans. She’s familiar with Thomas Hawkes because she has seen their advertisements in her magazines and newspapers. So on the Monday afternoon, now just two days after Madame X’s party, this lady in Peoria takes her horse and buggy over to her local boutique store and says to the boutique manager, “I would like a Thomas Hawkes cut glass punch bowl, too.”

Her order is taken by the boutique, which sends it through the US Mail. Years before, this might have taken weeks to make its way to its destination. But now this order takes only three days before it travels from Peoria to Corning. Just four weeks later, that cut glass punch bowl is completed in the Thomas Hawkes factory, and just one week after that, it is safely delivered to the home of the lady in Peoria.

This multitude of events could not have happened at any other place or any other time in history.

It was the numerous technological improvements all coming together in America. It was the desire to emulate both the wealthy and the Europeans. It was the discovery of silica in the United States. American glass success was due to European workers who had been trained since childhood in how to make beauty with their bare hands. It was due to a superior transportation infrastructure, as well as the ability to advertise. It was due to the mass transfer of wealth to America and the building of modern factories in America. And perhaps, most importantly, it is due to trans-cultural diffusion.

And that, in a nutshell, is why American Brilliant cut glass succeeded when and where it did.

Thank you.