A Matter of Destiny

Napoleon Bonaparte, the Emperor of France, and the most feared military leader in 19th-century Europe, believed in personal destiny.

When he crowned himself emperor in 1804, Napoleon truly believed he was fated to rule France, Europe — and he thought — the world. Before he was finally defeated in 1815, Napoleon had checked off the first two boxes, pulling most of Europe onto the map of the First French Empire, an era that remains a source of pride for many Frenchmen.

Napoleon’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte also believed in personal destiny. He believed it was his destiny to bring back Napoleonic rule — and, as emperor, to take on the projects that his uncle, Napoleon I, had not completed.

A Fanatical Obsession

Louis-Napoleon talked about his kismet for decades, assuring friends that it was in the cards that he would become the next French emperor. "I believe," Louis Napoleon wrote when in his twenties, "that from time to time, men are created whom I call volunteers of providence, in whose hands are placed the destiny of their countries. I believe I am one of those men…If I am right, then providence will put me into a position to fulfill my mission.”

Napoleon’s siblings, who had been kings and queens during the First French Colonial Empire, thought their nephew Louis-Napoleon was lost in flights of fancy, and refused to help him fulfill his supposed destiny as the next Bonaparte emperor.

However, via an unlikely and comical rise, Louis Napoleon brought his dreams to fruition. In 1852, three decades after Napoleon I died, his nephew took control of France tapping himself as Emperor Napoleon III — and unveiling the Second French Empire (1852-1870), the most opulent, sumptuous and over-the-top period France had ever known. Curiously, it’s mostly forgotten — for reasons that will soon be explained.

How Did Louis-Napoleon Rise from Dreamer to Emperor?

In 1812, when Napoleon I was about to head off on his most disastrous military operation ever — the ill-fated Russian campaign — his nephew Louis-Napoleon, then 4, implored him not to go saying it wouldn’t be good for France if Napoleon perished. “Keep your eye on that one,” Napoleon said to his attaché. “Someday he may well rule the French.”

His uncle’s comment made an impression on the boy, even though, at the time, he was third in line as Napoleon’s heir, the first being Napoleon’s son and the second in line being Louis-Napoleon’s older brother.

When Napoleon was defeated in 1815 and shipped off to St. Helena, he stipulated that his son become emperor of the French. The victors said no, but in the two weeks it took to get a French king on the throne, the boy — then four years old and living in Austria — was officially Emperor Napoleon II.

When Napoleon died in 1821, his son shunned the idea of trying to retake his father’s throne and died in 1832. Louis-Napoleon’s older brother had died in 1831 — which meant that Louis-Napoleon was now heir.

Napoleon’s son, Napoleon II after his two-week rule in 1815, had no desire to try to reestablish a Bonaparte empire in France. He’s shown here at age 7 in a painting attributed to Johann Peter Krafft circa 1818. M.S. Rau.

The Heir to Nothing is Called by Destiny

In 1832, France was ruled by King Louis-Philippe, and the Bonapartes had been banished from the country. Most of the family wanted to return to France and kept petitioning the French king, swearing that they had no desire to bring back Bonaparte rule.

But Louis-Napoleon believed his destiny was beckoning. In 1836, he galloped into Strasbourg, in eastern France, calling out to the residents that he was restoring Bonaparte rule, then charged down a dead-end street, where he and his cohorts were arrested.

Napoleon’s siblings and even his own father — Louis, who’d always suspected that Louis-Napoleon wasn’t his son — were furious at his ridiculous overthrow attempt, and mocked around the world. The French king banished him to the U.S., but Louis-Napoleon returned the next year when his mother, Hortense Beauharnais Bonaparte, long separated from her husband Louis, was dying.

Made extremely wealthy by her death, Louis-Napoleon moved to London, where he rode about in a fine carriage emblazoned with the imperial golden eagle and attended the most elite soirees.

A Second Stab to Grab the Reins

In 1840, when the French king brought back Napoleon’s remains from St. Helena, a momentous occasion when millions lined the banks of the River Seine in a final farewell, Louis-Napoleon saw a window.

He organized another coup d état, this time in Boulogne accompanied by 50 “fighters” — his servants, and those of his friends, dressed in fancy uniforms that he’d had made. Despite the pomp, his efforts were futile. Louis-Napoleon and his cohorts were arrested.

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, 32, was convicted of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment at the Fortress of Ham. Louis-Napoleon, who’d previously been lackadaisical in his studies, later called his prison “The University of Ham” because he read and wrote books while imprisoned.

Back to Exile in London

After six years, Louis-Napoleon escaped — and moved back to London. His lifestyle was less luxurious as he had blown through his inheritance. Opportunistically, he coupled with a wealthy courtesan, Harriet Howard, who bankrolled several propagandistic newspapers he had set up in France that churned out articles saying Louis-Napoleon should rule and detailed his studies of industry and urban design in London.

Not long after, in France an uprising called the 1848 French Revolution, which was violent but far less bloody than the 1789 revolution, chased out the king and brought in the Second Republic. In the first-ever election held with universal male suffrage, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, an escaped convict living in England, was voted in as the first president of France.

The Frustrated First President of France

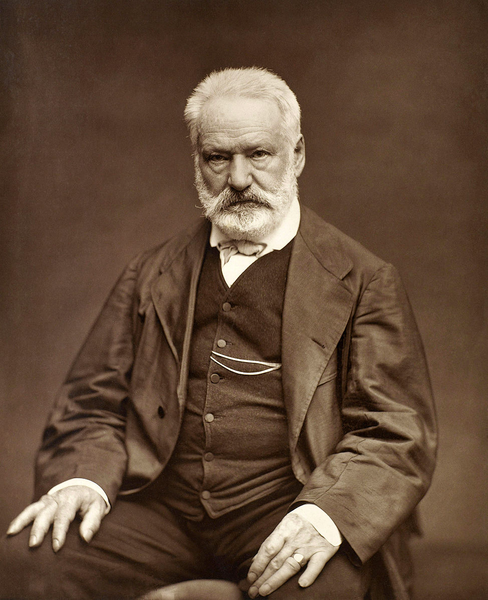

After moving to Paris, President Bonaparte was quickly frustrated in his attempts at reform. Initially, the writer Victor Hugo, who was also a parliamentarian, welcomed him. Louis-Napoleon promised Hugo the post of Education Minister, but then gave it to someone else. Outraged, powerful Hugo joined the parliamentary factions who blocked Louis-Napoleon’s plans.

In December 1851, President Bonaparte had accomplished little — and since presidents had only one four-year term, he couldn’t run for reelection. Instead, he overthrew his own government, initially saying he’d just stay on as president for another decade or so.

The next year he revealed what had been his plan all along: he proclaimed himself Emperor Napoleon III and the Second French Empire began. Hugo left France in disgust, going into self-imposed exile and attacking Louis-Napoleon, aka Napoleon III, in books and pamphlets printed abroad, calling him Napoleon the Small.

The Second Empire — More Dazzling than the First

When Napoleon I took power in 1804, he vowed to make Paris the most modern and beautiful city in the world. Bogged down by constant wars, however, Napoleon I never got around to fixing up the rat-infested, crowded and congested French capital.That promised renovation was a priority for his nephew. Napoleon III began his rule by hiring Georges-Eugene Haussmann, a French administrator, and together with architects and designers, they drew up plans for a revitalized Paris.

Before long, slums were taken down, wide boulevards were going in and uniform stone buildings, with wrought iron balconies and mansard roofs, were shooting up. The innovative use of modern materials has come to be known as Second Empire style and has inspired architecture in the decades to come. Second Empire architecture can be seen today across Europe, the United States, and Canada. Expansive, beautiful public parks dotted with lakes were created that became the site of picnics and daily promenades. Railroads soon crisscrossed the country and grand stations were unveiled; telegraphic lines enabled messages from thousands of miles away, and new ports greeted transatlantic steamers.

Aqueducts, canals and sewers went in — so did racetracks and new casino towns — and Napoleon III established new banks that gave loans to industry and small businesses, even to the lower classes. The economy began booming with new money — including from international tourism, which was skyrocketing — and a new merchant class emerged, along with department stores and the arrival of haute couture, which then included a bustle.

And in the city praised for its modernity — some now called Napoleon III “the emperor-magician” due to the dazzling changes being unveiled — Everyman began playing the Bourse along with the horses, and every wealthy man was seen strolling with a courtesan at his side.

The Belle of the Global Ball

The arts flourished — with or without the state support of the Paris Salons, where thousands of works were exhibited before an awed public. Balls, including masquerade balls, were weekly affairs, and operas and theatre productions were world-class, though some nightlife was rowdy.

Mark Twain, one of the 15 million visitors who poured in for the 1867 Universal Exhibition, when the elevator was among the novelties displayed, was one who was overwhelmed by the entertainment in Paris. He described the can-can thusly: “The idea of it is to dance as wildly, as noisily, as furiously as you can; expose yourself as much as possible if you are a woman; and kick as high as you can, no matter which sex you belong to.”

Between its culture, its vice, and the café-lined streets where organ grinders with monkeys and dancing bears performed, Paris became the world’s most international, colorful and modern city — the belle of the global belle. Powerful ambassadors, playboy princes and well-to-do Americans began flocking to the city that was even illuminated by tens of thousands of new gas lights.

Café Tortoni by Eugene von Guerard, 1856. Source.

The Emperor’s Achilles Heel

But while Napoleon III excelled at most domestic affairs — including instating mandatory schooling — his serious failing was foreign policy. His weak spot was his uncle’s greatest strength: military adventures. Napoleon III had no stomach for warring — he became nauseated on the battlefield — but he kept getting drawn into war after war, from the Crimean War to the bloody 1858 Battle of Solferino in Italy.Despite his half-cocked military moves with ill-defined motives, Napoleon III kept expanding territory into four continents, far further than Napoleon I. His fighters brutally seized territories in North Africa and Asia for the French, and Napoleon III even made good on his uncle’s desire to move into North America: in 1863, after Mexico defaulted on a loan, France seized it. During this time, France remained neutral during the American Civil War that raged on from 1861 to 1865. They kept their focus on their campaign in Mexico.

Second Serious Mistake

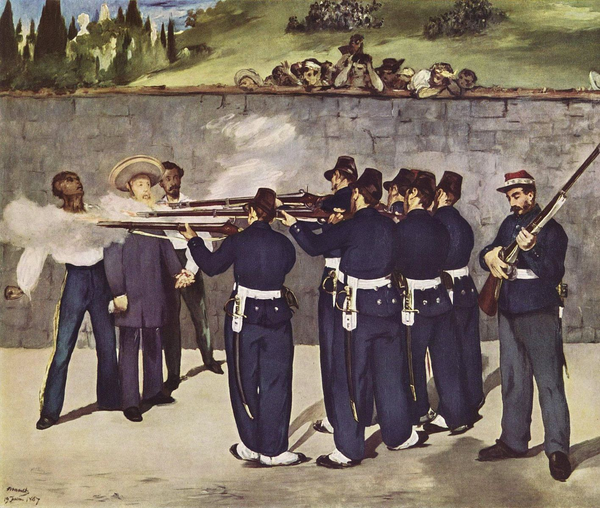

In his second-most foolish and tragic move in his entire reign, in 1864 Napoleon III sent Archduke Maximilian of Austria to reign as emperor in Mexico, propped up by the French army. Overextended militarily, Napoleon III withdrew military support in early 1867 — and Maximilian was assassinated by firing squad within three months. French society was horrified, and Edouard Manet memorialized the tragedy in a huge canvas, completed around 1868, that was predictably rejected for exhibition in the Paris Salon.As if this mistake was not detrimental enough, Napoleon III then fell for a trick played by Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck — involving which royal family would ascend to the Spanish throne, an altogether unimportant matter. Although the French military was by then severely depleted, France declared war on Prussia on July 16, 1870. The emperor, who insisted on fighting despite being extremely ill, was captured in the Battle of Sedan on September 2, and France promptly surrendered. The Second French Empire crashed overnight at the start of the Franco Prussian war.

The Siege of Paris

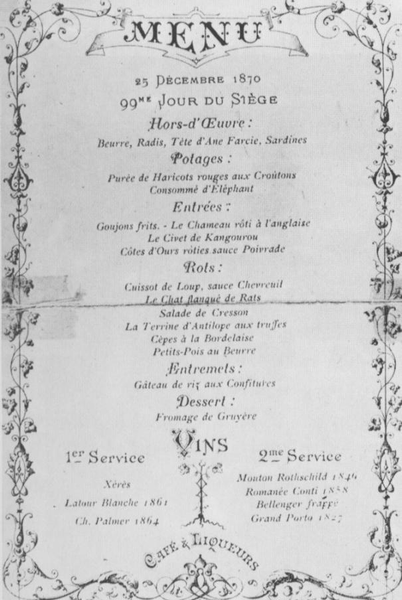

Meanwhile in Paris, where the government was in complete disarray, injured soldiers by the thousands poured in, dying in the streets. The hastily assembled new government of the French Third Republic foolishly opted to continue fighting, even though it was quickly encircled by Prussian forces, who prevented supplies from getting in during the four-month Siege of Paris. With food running out, the wealthy began dining on zoo animals, while most Parisians were forced to eat rats.

Plummeting so dramatically — from enjoying the most opulent lifestyle Parisians had ever known to subsisting on rodents — was shocking and horrifying, and the new France government blamed only one person for the fall: Napoleon III, who slunk back to England, dying there in 1873. When his long-time foe Victor Hugo finally returned to Paris, he wrote yet another book, The History of a Crime, excoriating the final Bonaparte ruler, which concluded, “Let us forget this man.”

And despite all the wonders that Napoleon III brought to France, that’s exactly what Frenchmen did.