Artists & Artisans

Picasso, Pablo

One could argue that Pablo Picasso was the most influential artist to have ever lived. He was certainly one of the most diverse, creating works of art in a dizzying array of styles and media throughout his nearly 80-year long career. Artists continue to emulate his works, while his prints and paintings hang in homes and museums around the world. His Les Femmes d'Alger ("Version O") claims a place among the ten most expensive paintings in the world, having achieved $179.4 million at auction in 2015. But his legacy runs far deeper than simple dollar and cents can describe.

Though some critics claim faults in certain periods of his work or even his personal relationships, he unquestionably remains one of the most consummate geniuses in the whole of art history. Read on to learn more about the life and development of this master of his craft.

CHILDHOOD AND EARLY LIFE

Born on October 25, 1881, in Málaga, Spain, Pablo Picasso was the son of the academic painter José Ruiz Blasco. He grew up surrounded by art, and naturally he began drawing at an early age. Thanks to the teachings of his father, he was skilled in oil painting by the young age of eight. His earliest known painting, The Picador, was composed by the artist in 1890 at that same age; amazingly, the bullfighter was a theme that he would return to time and time again throughout his career.

In 1895, Picasso and his family moved to Barcelona, where he studied at La Lonja, the academy of fine arts. At the age of 17, he became closely associated with the group of modernists who gathered at the café Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats), including the Catalan Carlos Casagemas (1880–1901). Picasso’s first exhibition took place in Barcelona in 1900, and that fall he traveled to Paris for the very first time, dramatically expanding his artistic circle.

His earliest paintings from this period largely reflect the influence of his father. Executed in an academic style, they differ significantly from the paintings that are associated with the artist today. However, at the dawn of the 20th century, his style would take a significant turn towards modern art.

BLUE PERIOD (1901-1904)

It is believed that the suicide of Picasso’s friend, Casagemas, is what spurred the first great stylistic period of the artist's career. Known as the Blue Period, it began in late 1901 and lasted for about three years when he lived intermittently between Paris and Spain. Named for the blue and grey color palette that pervaded these works, Picasso's creations during this time tended towards themes of poverty, seclusion and melancholy. The Picasso painting considered the first of the Blue Period, The Death of Casagemas (Musée Picasso, Paris), reflects the profound psychological impact of the unexpected suicide of his friend, after which Picasso sank into a deep depression.

Lonely figures with El Greco-like features, such as his famed The Old Guitarist from 1903 (Art Institute of Chicago), characteristic of this collection. Though they were difficult for the artist to sell at the time, Picasso's Blue Period paintings are among his most popular and highly prized today.

ROSE PERIOD (1904-1906)

The fog gradually began to lift away from Picasso's paintings and his life around 1904. At this time, Picasso had moved to Montmartre, a neighborhood in Paris that had become the epicenter of artistic life in the city. Picasso's small circle of friends - including the artist Georges Braque, the wealthy Gertrude Stein, and the avant-garde writers Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire - gloried in the exclusiveness of community. And at the center of it all was Pablo Picasso.

Warmer colors began to move back into his works, beginning with his short-lived but important Rose Period. Perhaps inspired by the bohemian characters who lived and worked in Montmartre, many of these paintings depicted entertainers such as harlequins and circus performers.

Perhaps the most important change in Picasso's life during this period was the dedicated patronage of Gertrude and Leon Stein. The American siblings held weekly salons in their home, which became a breeding ground for intellectual, modernist theory. Picasso's portrait of Gertrude, painted around 1905-06, is perhaps his best-known work from this important period. Portraying her face like a mask, it reveals his recent encounter with Iberian art and portends the changes to come in his style.

AFRICAN PERIOD (1906-1909)

While his Rose Period marks the beginning of Picasso's experimentation with primitivism, it wasn't until late 1906 when this distinctive style became fully developed. Known as his African Period, this three-year span was largely defined by Picasso's encounters with and interpretation of African sculpture, traditional African masks and ancient Egyptian art. Arguably his greatest masterpiece - Les Demoiselles d'Avignon - was created during this period. The two figures on the right of the canvas are particularly evocative of African masks, though the work also reveals Picasso's interpretation of Ingres in his treatment of the nude figures.

The work is also indicative of one of his greatest departures from the traditions of Western art. In the painting, Picasso has entirely abandoned perspective in favor of a flattened pictorial plane. Furthermore, his angular interpretation of the figures and their position in space presage his revolutionary Cubist style.

CUBISM (1908-1914)

Cubism has been called a revolution in the modern arts, the likes of which had not been seen since the Renaissance. Yet, unlike the Renaissance, true Cubism was a private, esoteric art that was created by two painters almost solely for themselves and a small circle of intimates. Those painters were, of course, Pablo Picasso and his colleague Georges Braque.

It is widely recognized that Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon was the beginning of Cubism, though the piece is placed firmly within his "African Period." Yet, it was this oil painting that influenced Braque's Nude of 1907-08, setting the artist on a path towards the Cubist style that he developed by 1908. Picasso took note of Braque's innovations, and from there the style evolved through several transformations as the two artists worked side by side. Braque described his time he spent with Picasso: "We lived in Montmartre, we saw each other every day, we talked. During those years, Picasso and I discussed things which nobody will ever discuss again, which nobody else would know how to discuss, which nobody else would know how to understand."

From early in 1909, Braque and Picasso had successfully developed a cohesive, early Cubist style based on their aesthetic theories. Abandoning traditional perspective, they instead explored the multiple "facets" of an object as it exists in a flattened plane. Some of Picasso's cubist artwork used pasted paper fragments, introducing the first collages to the fine art world. Wholly innovative and unique, Cubism undoubtedly paved the way for the abstract artists of the next generation.

NEOCLASSICISM (1917-1925)

Interestingly, following the start of World War I, Picasso reverted to more traditional styles and subjects, moving away from his experimentations with Cubism. During this period, which has been called his “return to order,” he explored the classical themes and forms that have pervaded art history for centuries. It was likely his first visit to Italy in 1917 that served as the impetus for this stylistic change. For the first time, he encountered the works of the Renaissance artists in the flesh. Soon thereafter, minotaurs, nymphs, centaurs and other mythological creatures began to appear in his paintings, which took on a new monumentality and classicism that was inspired by paintings from the Renaissance age.

SURREALISM (1925-1932)

After his brief period of relatively realistic representation, Picasso dove head first into another period of experimentation, adopting the Surrealist style. The co-founder and unofficial leader of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, released his now-legendary Surrealist manifesto in 1924; by 1925, Breton declared Picasso as “one of ours.” Picasso adopted the new artistic theory with gusto, composing dreamy depictions of distorted figures with twisted features and bodies. Their “surreality” was enhanced by Picasso’s unnatural palette, which brought together bright, clashing colors. It also revived his interest in Cubism and primitivism — perspective once again became disjointed, while clashing organic and geometric forms dominated his compositions.

LATER LIFE

After his Surrealist period, Picasso would go on to create artwork for the next 40 years until his death in 1973. Perhaps the greatest masterpiece of this period was his massive 1937 oil on canvas Guernica (Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid). Alongside Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Guernica is arguably the work for which Picasso was most famous. Executed in muted tones of black, blue and grey, the composition was painted in response to the bombing of Guernica, a Basque Country town in northern Spain, by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The bombing particularly hit home for the Spanish-born Picasso, and his anguish over the the devastation is visceral in this work that has been praised as the greatest anti-war painting ever made.

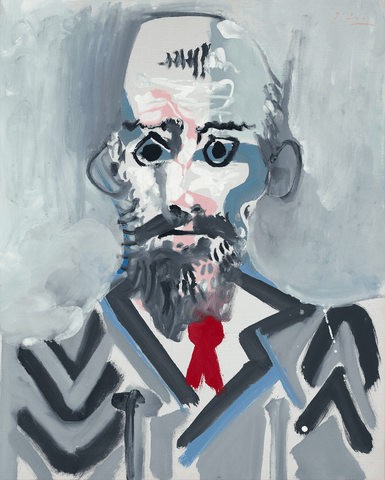

In the later years of his life, Picasso increasingly turned to portraiture that was evocative of his earlier styles, including an important series of self-referential portraits. The mid-1960s witnessed an outpouring of productivity from the artist. Although he was in his 80s, Picasso enjoyed a youthful energy that ultimately compelled him to embark on a creative reimagining of himself at various points in his life. In some of these self portraits, he would portray himself as a disheveled, bearded old man, or even as the tough worker or fisherman he so admired throughout his career. These powerful works remain highly coveted by collectors, with Pablo Picasso original art continuing to draw global attention at major auctions. They represent the perfect, final achievement of an artistic genius that remains unmatched.

Pushing the boundaries of his own creativity throughout his long career, Picasso devoted himself to artistic production. The result was one of the richest and most important oeuvres in art history.

Artists & Artisans

Picasso, Pablo

One could argue that Pablo Picasso was the most influential artist to have ever lived. He was certainly one of the most diverse, creating works of art in a dizzying array of styles and media throughout his nearly 80-year long career. Artists continue to emulate his works, while his prints and paintings hang in homes and museums around the world. His Les Femmes d'Alger ("Version O") claims a place among the ten most expensive paintings in the world, having achieved $179.4 million at auction in 2015. But his legacy runs far deeper than simple dollar and cents can describe.

Though some critics claim faults in certain periods of his work or even his personal relationships, he unquestionably remains one of the most consummate geniuses in the whole of art history. Read on to learn more about the life and development of this master of his craft.

CHILDHOOD AND EARLY LIFE

Born on October 25, 1881, in Málaga, Spain, Pablo Picasso was the son of the academic painter José Ruiz Blasco. He grew up surrounded by art, and naturally he began drawing at an early age. Thanks to the teachings of his father, he was skilled in oil painting by the young age of eight. His earliest known painting, The Picador, was composed by the artist in 1890 at that same age; amazingly, the bullfighter was a theme that he would return to time and time again throughout his career.

In 1895, Picasso and his family moved to Barcelona, where he studied at La Lonja, the academy of fine arts. At the age of 17, he became closely associated with the group of modernists who gathered at the café Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats), including the Catalan Carlos Casagemas (1880–1901). Picasso’s first exhibition took place in Barcelona in 1900, and that fall he traveled to Paris for the very first time, dramatically expanding his artistic circle.

His earliest paintings from this period largely reflect the influence of his father. Executed in an academic style, they differ significantly from the paintings that are associated with the artist today. However, at the dawn of the 20th century, his style would take a significant turn towards modern art.

BLUE PERIOD (1901-1904)

It is believed that the suicide of Picasso’s friend, Casagemas, is what spurred the first great stylistic period of the artist's career. Known as the Blue Period, it began in late 1901 and lasted for about three years when he lived intermittently between Paris and Spain. Named for the blue and grey color palette that pervaded these works, Picasso's creations during this time tended towards themes of poverty, seclusion and melancholy. The Picasso painting considered the first of the Blue Period, The Death of Casagemas (Musée Picasso, Paris), reflects the profound psychological impact of the unexpected suicide of his friend, after which Picasso sank into a deep depression.

Lonely figures with El Greco-like features, such as his famed The Old Guitarist from 1903 (Art Institute of Chicago), characteristic of this collection. Though they were difficult for the artist to sell at the time, Picasso's Blue Period paintings are among his most popular and highly prized today.

ROSE PERIOD (1904-1906)

The fog gradually began to lift away from Picasso's paintings and his life around 1904. At this time, Picasso had moved to Montmartre, a neighborhood in Paris that had become the epicenter of artistic life in the city. Picasso's small circle of friends - including the artist Georges Braque, the wealthy Gertrude Stein, and the avant-garde writers Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire - gloried in the exclusiveness of community. And at the center of it all was Pablo Picasso.

Warmer colors began to move back into his works, beginning with his short-lived but important Rose Period. Perhaps inspired by the bohemian characters who lived and worked in Montmartre, many of these paintings depicted entertainers such as harlequins and circus performers.

Perhaps the most important change in Picasso's life during this period was the dedicated patronage of Gertrude and Leon Stein. The American siblings held weekly salons in their home, which became a breeding ground for intellectual, modernist theory. Picasso's portrait of Gertrude, painted around 1905-06, is perhaps his best-known work from this important period. Portraying her face like a mask, it reveals his recent encounter with Iberian art and portends the changes to come in his style.

AFRICAN PERIOD (1906-1909)

While his Rose Period marks the beginning of Picasso's experimentation with primitivism, it wasn't until late 1906 when this distinctive style became fully developed. Known as his African Period, this three-year span was largely defined by Picasso's encounters with and interpretation of African sculpture, traditional African masks and ancient Egyptian art. Arguably his greatest masterpiece - Les Demoiselles d'Avignon - was created during this period. The two figures on the right of the canvas are particularly evocative of African masks, though the work also reveals Picasso's interpretation of Ingres in his treatment of the nude figures.

The work is also indicative of one of his greatest departures from the traditions of Western art. In the painting, Picasso has entirely abandoned perspective in favor of a flattened pictorial plane. Furthermore, his angular interpretation of the figures and their position in space presage his revolutionary Cubist style.

CUBISM (1908-1914)

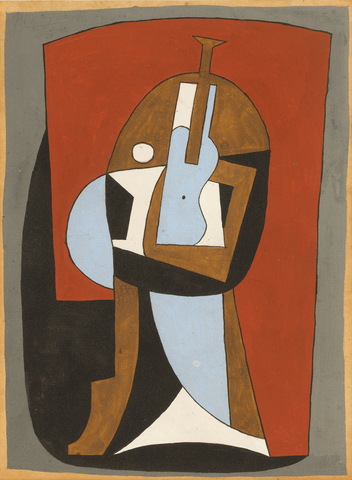

Cubism has been called a revolution in the modern arts, the likes of which had not been seen since the Renaissance. Yet, unlike the Renaissance, true Cubism was a private, esoteric art that was created by two painters almost solely for themselves and a small circle of intimates. Those painters were, of course, Pablo Picasso and his colleague Georges Braque.

It is widely recognized that Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon was the beginning of Cubism, though the piece is placed firmly within his "African Period." Yet, it was this oil painting that influenced Braque's Nude of 1907-08, setting the artist on a path towards the Cubist style that he developed by 1908. Picasso took note of Braque's innovations, and from there the style evolved through several transformations as the two artists worked side by side. Braque described his time he spent with Picasso: "We lived in Montmartre, we saw each other every day, we talked. During those years, Picasso and I discussed things which nobody will ever discuss again, which nobody else would know how to discuss, which nobody else would know how to understand."

From early in 1909, Braque and Picasso had successfully developed a cohesive, early Cubist style based on their aesthetic theories. Abandoning traditional perspective, they instead explored the multiple "facets" of an object as it exists in a flattened plane. Some of Picasso's cubist artwork used pasted paper fragments, introducing the first collages to the fine art world. Wholly innovative and unique, Cubism undoubtedly paved the way for the abstract artists of the next generation.

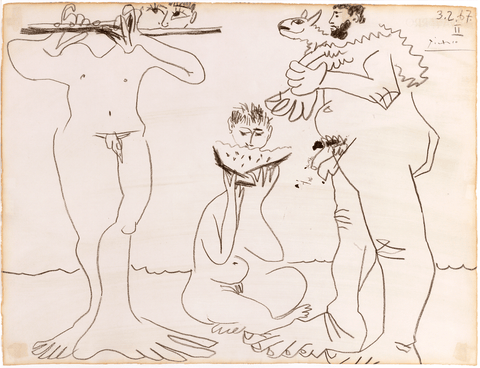

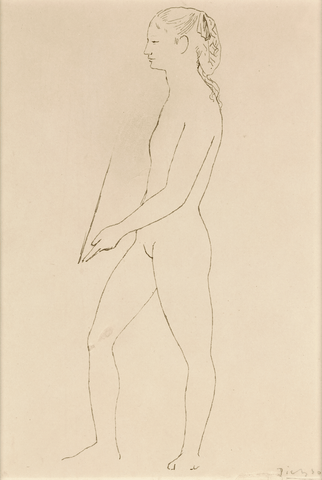

NEOCLASSICISM (1917-1925)

Interestingly, following the start of World War I, Picasso reverted to more traditional styles and subjects, moving away from his experimentations with Cubism. During this period, which has been called his “return to order,” he explored the classical themes and forms that have pervaded art history for centuries. It was likely his first visit to Italy in 1917 that served as the impetus for this stylistic change. For the first time, he encountered the works of the Renaissance artists in the flesh. Soon thereafter, minotaurs, nymphs, centaurs and other mythological creatures began to appear in his paintings, which took on a new monumentality and classicism that was inspired by paintings from the Renaissance age.

SURREALISM (1925-1932)

After his brief period of relatively realistic representation, Picasso dove head first into another period of experimentation, adopting the Surrealist style. The co-founder and unofficial leader of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, released his now-legendary Surrealist manifesto in 1924; by 1925, Breton declared Picasso as “one of ours.” Picasso adopted the new artistic theory with gusto, composing dreamy depictions of distorted figures with twisted features and bodies. Their “surreality” was enhanced by Picasso’s unnatural palette, which brought together bright, clashing colors. It also revived his interest in Cubism and primitivism — perspective once again became disjointed, while clashing organic and geometric forms dominated his compositions.

LATER LIFE

After his Surrealist period, Picasso would go on to create artwork for the next 40 years until his death in 1973. Perhaps the greatest masterpiece of this period was his massive 1937 oil on canvas Guernica (Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid). Alongside Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Guernica is arguably the work for which Picasso was most famous. Executed in muted tones of black, blue and grey, the composition was painted in response to the bombing of Guernica, a Basque Country town in northern Spain, by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The bombing particularly hit home for the Spanish-born Picasso, and his anguish over the the devastation is visceral in this work that has been praised as the greatest anti-war painting ever made.

In the later years of his life, Picasso increasingly turned to portraiture that was evocative of his earlier styles, including an important series of self-referential portraits. The mid-1960s witnessed an outpouring of productivity from the artist. Although he was in his 80s, Picasso enjoyed a youthful energy that ultimately compelled him to embark on a creative reimagining of himself at various points in his life. In some of these self portraits, he would portray himself as a disheveled, bearded old man, or even as the tough worker or fisherman he so admired throughout his career. These powerful works remain highly coveted by collectors, with Pablo Picasso original art continuing to draw global attention at major auctions. They represent the perfect, final achievement of an artistic genius that remains unmatched.

Pushing the boundaries of his own creativity throughout his long career, Picasso devoted himself to artistic production. The result was one of the richest and most important oeuvres in art history.