Matisse's Art

One of the 20th century’s greatest artistic minds, Henri Matisse stands as a towering figure of modern art. He is renowned for his bold use of color as the founder of Fauvism, his innovative composition and expressive forms primarily in the medium of painting. The vivid movement and color in Matisse’s art heavily influenced artists including Andre Brasilier.

Matisse’s exploration of printmaking, however, played a crucial role in his artistic evolution and is an important part of his legacy today. Read on to explore Matisse's most experimental and innovative print works that profoundly shaped his artistic vision and left an indelible mark on art history.

Dance (I) by Henri Matisse. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Source.

Henri Matisse: Modern Master

Matisse's significance as a titan of art history cannot be overstated. Born in 1869 in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, France, Matisse's artistic career spanned over 60 years, during which he continually pushed the boundaries of expression and form.Prolific and endlessly innovative until he died in 1954, the French artist's contributions to the avant-garde were boundless, from his founding role in the Fauves to his experimentations in nearly every media, including painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking and cut-outs. As the descendant of a long line of weavers and an avid textile collector, it is no surprise that Matisse relished continuously pushing the traditional boundaries of artistic materials and pictorial forms.

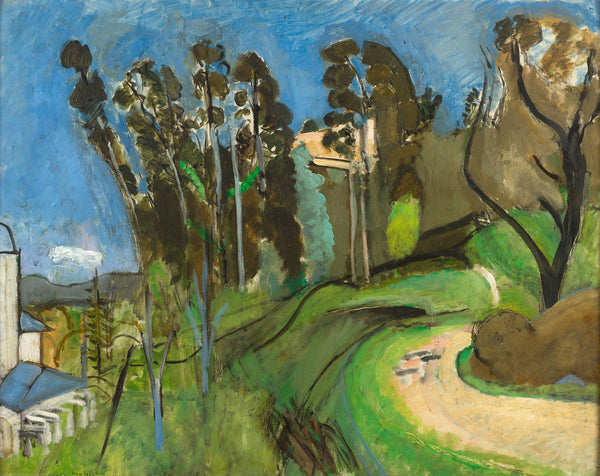

Radical Invention: 1913-1917

The period between 1913 and 1917 marked a significant moment in Matisse's career, characterized by experimentation and innovation. Against the backdrop of World War I and the rise of Cubism, Matisse returned to printmaking with renewed vigor, seeking to redefine his artistic language and challenge conventional norms.

Recent scholarship and major museum exhibitions have revisited this pivotal period between the artist’s return from Morocco and his departure for Nice in 1917, understanding the work to be much more than a mere abnormality in his oeuvre caused by the effects of World War I and his friendly rivalry with Picasso.

Matisse himself would go on to reveal the importance of these years when he identified two works—Bathers by a River (1909–10, 1913, 1916–17) and The Moroccans (1915–16)—as among his most "pivotal." His re-engagement with printmaking during this period, then, was part of his ongoing quest for artistic renewal and reinvention.

Nude with Moroccan Mirror by Henri Matisse. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Source.

Matisse and Printmaking

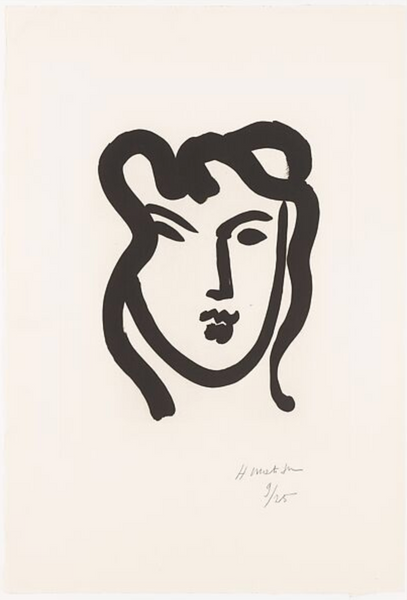

Beginning as early as 1900, Matisse would complete more than 800 prints throughout his career in a wide variety of techniques, including woodcuts, linoleum cuts, lithographs and monotypes.

These methods were an integral extension of his painting practice, and the discoveries in texture, line and color that Matisse made in prints often quickly made appearances in his paintings, and vice versa. For the master innovator, prints were a place to experiment with the most basic elements of composition and to repeatedly explore the visual purity that he sought throughout his oeuvre.

Matisse’s approach to printmaking was uniquely intimate and personal. Rather than relying on master printers, he worked primarily on his in-studio etching press and was deeply connected to the printing process himself. The intimate nature of Matisse's printmaking is evident not only in his working methods but also in his choice of subjects, which focused on portraits of friends and family, nudes and simplistic still-lifes.

Matisse’s daughter, Marguerite, often worked with her father in his Paris studio, and she later noted the impact printmaking had on Matisse’s overall vision, recalling the “great moment of emotion at the instant when we discovered the imprint on the sheet of paper.”

Still Life with Goldfish I by Henri Matisse. M.S. Rau.

Monotypes

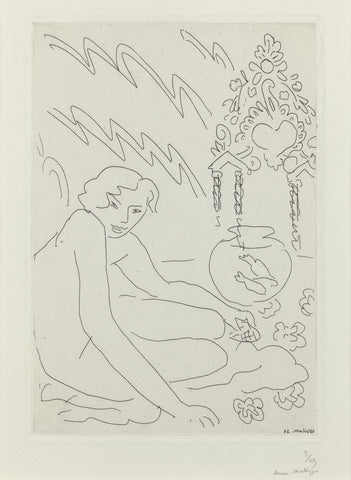

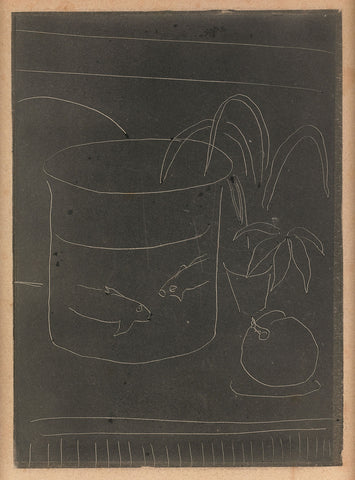

Central to Matisse's printmaking practice during this period were monotypes, a technique that allowed for spontaneous and expressive mark-making. Unlike printmaking methods that allow for the production of multiple, editioned prints, monotypes are printed through a transfer process that creates just one, unique work of art.

Matisse made his monotypes by covering a copper plate in black ink, then lightly and swiftly scratching into the pigment with a sharp tool to create his drawing that emerges in black and white after the plate is run through the press. The fluidity and immediacy of this medium allowed him to closely observe and repeatedly reduce his subjects to their essential forms, capturing their essence with remarkable clarity and energy.

Although it was a brief foray—Matisse only made 69 monotypes in his life—the stylistic influence of this technique still had a lasting impact on his work for decades to come. He soon began incising into the surface of his canvases, simplifying outlines, suppressing details, and employing black to express a tension between positive and negative space.

Interior with Goldfish by Henri Matisse. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Source.

Matisse's Goldfish

Among Matisse's most compelling works in printmaking is the series of six goldfish monotypes created between 1914 and 1915. These prints display the artist's virtuosic command of light and composition, while also showing his intense observation of and preoccupation with these aquatic creatures. Masterful paintings from the same period, such as Interior with Goldfish, perfectly demonstrate how Matisse translated the lessons learned in his prints to his paintings.The goldfish motif was especially important to Matisse, appearing frequently during the 1910s in more than nine major paintings and many more drawings and prints. To the artist, they held a multitude of meanings and visual functions. Their radiant orange, iridescent hues suited his exploration of pure color in his canvases, and their water-filled glass containers challenged his interest in rendering transparency and light.

As you can see in Interior with Goldfish, the subtle pinks and green of the buildings and open paint cans that surround the fish bowl allow the goldfish to pop within the bowl and the blue of the room. Matisse's gentle infusion of life and vitality, by way of the goldfish, creates a soothing and calming influence on what could have been a troubling or depressing subject matter. This was the art of balance with Matisse so mastered.

Metaphorically, the goldfish also represented an idyllic Golden Age, inspired hypnotic contemplation, and acted as a stand-in for the artist himself. Confined to his studio just as the goldfish to its bowl, Matisse felt a kinship with the fish who interacted with the world around them in a purely visual sense, observing and looking for truth and meaning.

Matisse’s Printmaking Legacy

In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the importance of printmaking in Matisse's career and legacy. Major museum exhibitions and scholarly publications have shed new light on this aspect of his practice, emphasizing its significance in shaping his artistic development and overall output.Collections of Matisse's prints can be found in prestigious institutions around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. These holdings attest to the enduring appeal and influence of Matisse's printmaking, ensuring that his legacy as an artistic innovator and master of the medium continues to resonate with audiences today.

Henri Matisse's exploration of printmaking represents a fascinating chapter in the history of modern art, showcasing his boundless creativity and innovative spirit. From his early experiments with monotypes to his later forays into lithography and linocut, Matisse's printmaking practice exemplifies his relentless pursuit of artistic innovation. By embracing printmaking and other material experimentation, Matisse placed himself among true visionaries of modern art.