Much like Midnight in Paris (2011), we can embark on a journey that transcends time and space, encountering the personification of Salvador Dalí or recontextualizing how we view an artwork through the protagonist’s eyes. Join me as we walk through the inclusion of art history in movies, infusing each frame, like a canvas, with an added layer of history and imagination.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986)

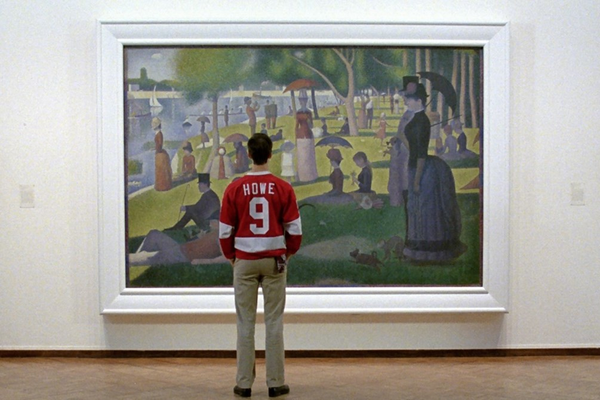

A Still from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Dir. by John Hughes. 1986.

Released almost forty years ago, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off remains an integral part of pop culture that continues to entertain both young and old audiences. With Chicago as its filming location, the feel-good movie follows Ferris Bueller on a raucous adventure as he skips school to roam around the city with his friends.

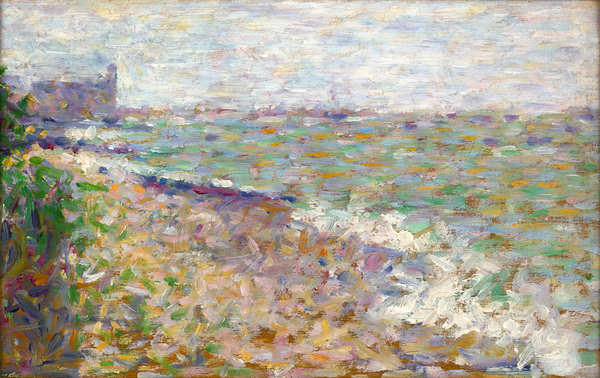

Along the way, the troupe stops at the Art Institute of Chicago, now the most famous movie set from the film, to admire the modernist artworks of Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso and Georges Seurat on display. Born from the director John Hughes’ admiration of the museum, the scene is rife with whimsical introspectiveness. While Ferris and his girlfriend Sloane kiss in front of a Chagallian stained glass window, Cameron focuses on Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884).

A Still from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off featuring Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte. Dir. by John Hughes. 1986.

This slowed-down and pensive scene at the Art Institute is a pause from the otherwise comedic scenes that drive the movie’s plot forward— it centers on Cameron’s personal evolution. Shot in a music video style with lengthy close-ups, the camera cuts back and forth between Cameron and the young girl’s face in the painting.

Hughes said of Seurat’s pointillist work, “I always thought this painting was sort of like making a movie, the pointillist style. You don’t have any idea what you’ve made until you step back... The more he looks at it, the more is there. He [Cameron] fears that the more you look at him, the less you see.” Through Cameron’s deep introspection, Hughes shows the viewer the emotional power that artwork can have if you take the time to absorb it.

Notting Hill (1999)

A Still from Notting Hill. Dir. by Roger Michelle. 1999.

In the movie Notting Hill, the painting La Mariée by Marc Chagall holds a pivotal significance in the plot, serving as both a catalyst for character development and a symbol of romantic yearning. In the film, the protagonist William Thacker, played by Hugh Grant, finds his humble life as a bookstore clerk interrupted by a whirlwind romance with the famous American actress Anna Scott, portrayed by Julia Roberts.

Early on in the movie, when William and Anna are first getting to know one another, the two discuss the post of Chagall’s work on the wall of William’s flat. The painting is an ode to young love, with a man embracing a young woman in a white veil. Her red dress contrasts with the blue background, pinning her as the focus.

Near the film's end, Anna purchases the original Chagall composition to proclaim her love for William. This comes as a shock not only to William but the viewer as well because she had shown up unexpectedly with the painting after almost a year of no contact before professing the iconic line, “I'm just a girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her.

The screenwriter Richard Curtis chose the painting because it “depicts a yearning for something that’s lost.” The choice to use a Chagall painting is fitting because it aligns seamlessly with the whirlwind romance and longing present throughout the film.

Les Fleurs des Amoureux sur Fond Multicolore by Marc Chagall. Circa 1978. Gouache, tempera and lithographic pencil on paper. M.S. Rau.

In his oeuvre, Chagall frequently explores themes of love, especially by depicting couples embracing, as seen in another work, Les Fleurs des Amoureux sur Fond Multicolore. With vibrant hues and floral still life next to couples embracing, the work is a moving meditation on love. His sonorous colors, figures that seem to float through space, and fantastical landscapes mirror the whimsical, whirlwind romance of the protagonists.

Like Chagall said, “In our life there is a single color, as on an artist’s palette, which provides the meaning of life and art. It is the color of love.” The dreamlike quality of La Mariée echoes the chance encounter between a humble London bookseller and an American movie star.

Midnight in Paris (2011)

In Woody Allen’s enchanting film Midnight in Paris, the intertwining of art, history and cinema takes center stage with the protagonist’s journey through time becomes a hilarious encounter with the biggest artists and writers of the early 20th century. In the movie, screenwriter Gil Pender, played by Owen Wilson, vacations in Paris with his fiancée while enduring a mid-life career crisis.

Unsatisfied with his kitschy Hollywood job, Gil takes to touring the city on his own. On one lonesome evening excursion, Gil encounters a group of strange yet familiar revelers who take him back in time to the Jazz Age. He finds himself mingling alongside the likes of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Pablo Picasso and Gertrude Stein. Stein, an American expatriate who hosts prominent writers and artists in makeshift salons at her home, becomes a mentor to Gil when she provides feedback on his new and daring book manuscript. The more time Gil spends in the 1920s, the more he realizes his deep dissatisfaction with the present.

A Still of Salvador Dalí (Adrien Brody) in Midnight in Paris. Dir. by Woody Allen. 2011.

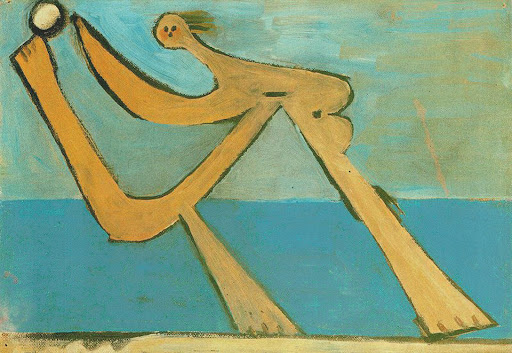

Baigneuse à Dinard by Pablo Picasso. 1928. Oil on Canvas. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes.

In one scene, Gil discusses his tumultuous relationship with Picasso’s current muse, Adriana, who in the film is the inspiration for his iconic painting Baigneuse à Dinard (1928). When she leaves the restaurant, Gil is invited to dine with Salvador Dalí, Man Ray and Luis Buñuel.

The group pokes fun at Dalí‘s surrealist art process when he asks Gil, “Do you think about the shape of the rhinoceros?... I paint rhinoceros. I paint you. Your sad eyes and big lips, melting over the hot sand, with one tear. Yes! And in your tear, another face. The Christ face! Yes! And the rhinoceros...”

While Allen comically explores Dalí’s artistic creation, the film correctly identifies the spirit of surrealism. Much like Gil yearns for the simplicity of the past, surrealism attempted to deal with the traumas of the post-World War I era by making untraditional art that pushed the boundaries of discernable reality.

Detail of Venus de Milo aux Tiroirs by Salvador Dalí. Cast in 1988. Bronze. M.S. Rau.

The sculpture Venus de Milo aux Tiroirs (1988) reflects Dalí‘s attempt to reconfigure reality by uniting different elements of history with domestic life. The famed Surrealist transformed Aphrodite, the well-known second-century BCE marble sculpture now in the Louvre, by adding drawers that pierce the goddess’ forehead, chin, breasts and torso.

Dalí ideated the first conception of this sculpture in a 1931 essay, writing that it was “created wholly for the purpose of materializing, in a fetishistic way, with maximum tangible reality, ideas and fantasies of a delirious character.” Dalí frequently appropriated classical imagery, as realized in this seven-foot-tall statue, because of his desire to situate his artistic practice as opposite to tradition.

Instead of adhering to the constraints of the corporeal world, Dalí constructs a dream-like fantasy where the drawers open the viewer up to the goddess’ subconscious. Like Sigmund Freund analogized psychoanalysis to opening drawers, Dalí investigates the psychological desire for love and sensuality. This is also the spirit of Gil’s time-traveling adventure, where he questions whether he truly loves his fiancée or is settling for a simplistic life he does not want.

Art Inspires Art

Cinema, whether a comedy or a contemplative romance, utilizes iconic artworks to explore the key themes of the major motion picture. These three films clearly show that art and cinema can have a symbiotic relationship. Just as a painting or sculpture can evoke emotions and provoke epiphatic thoughts, a film can immerse audiences in a thematically engaging experience.The timeless beauty of works by Marc Chagall and Salvador Dalí, whose visionary pieces transcend reality and invite us to explore the depths of our consciousness, work to reflect the inner dilemmas of the protagonists. Among these films, the artworks and artists function as tools for the characters to look introspectively at their lives and consider their happiness. Whether it be teenage angst or the question of true love, art and cinema’s interconnectedness is rooted in their visual storytelling and creative expression.